Power to the People is a column by D. Maurice Kreis, New Hampshire’s Consumer Advocate. Kreis and his staff of four represent the interests of residential utility customers before the NH Public Utilities Commission and elsewhere. It is co-published by Manchester Ink Link and InDepthNH.org.

By D. Maurice Kreis, Consumer Advocate

May 7, 1979, is a day which will live in infamy. But only if you’re a shareholder of an investor-owned utility.

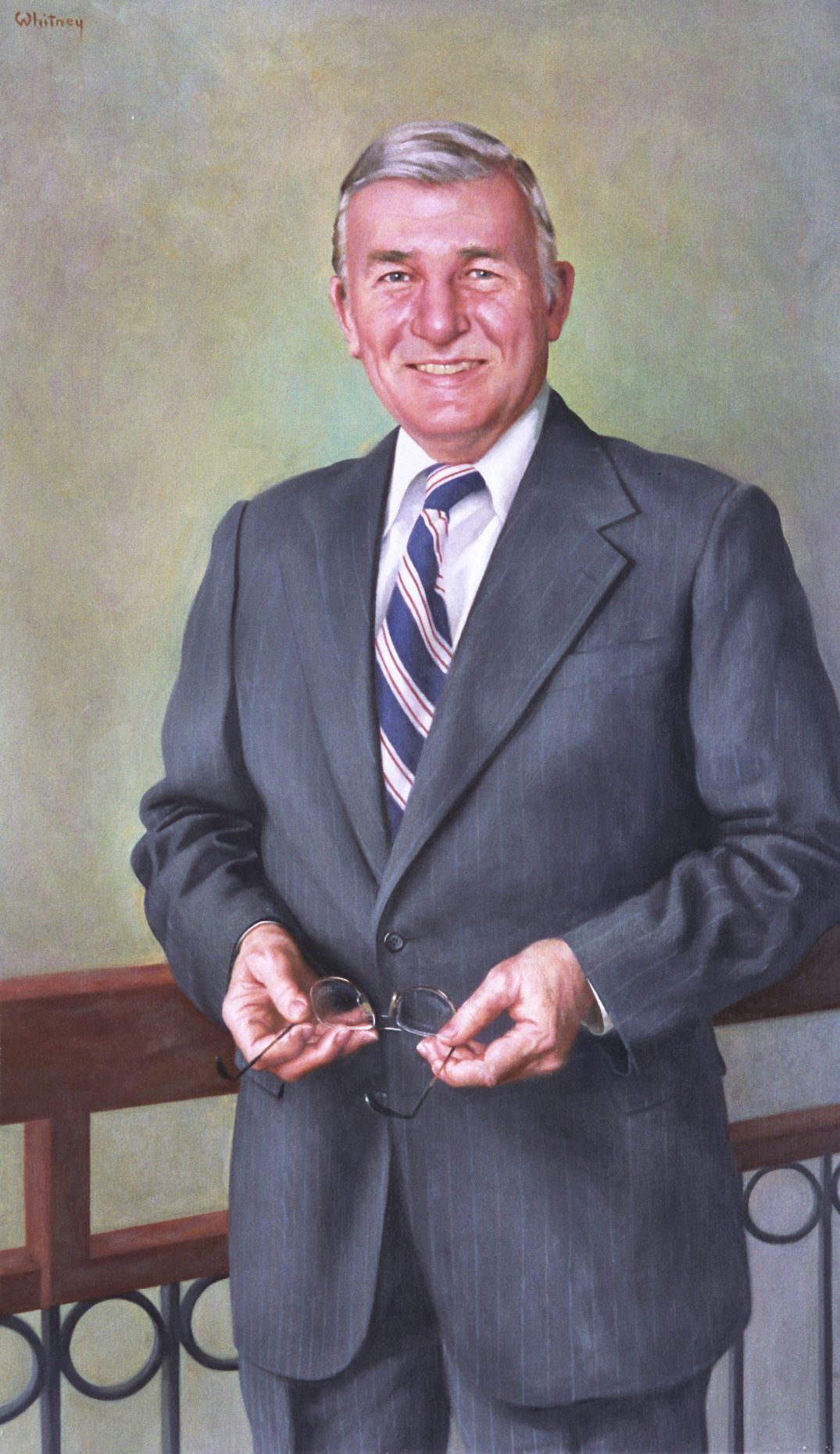

It was on May 7, 1979, that Governor Hugh Gallen signed into law what became RSA 378:30-a – New Hampshire’s world famous “anti-CWIP” statute.

Okay, maybe it’s only world famous among those who study how the rates of regulated monopolies are determined by the New Hampshire Public Utilities Commission (PUC) and its counterparts in other states and the federal government. CWIP is an acronym for “construction work in progress.”

Still, the anti-CWIP statute is an important slice of Granite State history. For one thing, it was the issue that catapulted Gallen to an upset victory in the 1978 gubernatorial election that ousted three-term incumbent Meldrim Thomson. For another, the anti-CWIP statute led inexorably to Public Service Company of New Hampshire (PSNH) nine years later becoming the first electric utility to go bankrupt since the Great Depression.

And on top of that, RSA 378:30-a is, to a lawyer’s eyes, the pinnacle of legislative clarity. Such clarity is a rare commodity indeed within the 40 or so bound volumes that comprise the New Hampshire Revised Statutes Annotated (RSAs).

To understand just how unambiguously unambiguous RSA 378:30-a truly is, in all of its unambiguousness, consider the three sentences of this law as they appear in RSA Title 34, home to all of the PUC’s enabling statutes.

The first sentence: “Public utility rates or charges shall not in any manner be based on the cost of construction work in progress.”

This seems lucid enough. But maybe it’s susceptible to more than one interpretation? So the drafters of RSA 378:30-a added a second sentence: “At no time shall any rates or charges be based upon any costs associated with construction work if said construction work is not completed.”

Perhaps there’s still some mischief left between the lines of those two sentences in RSA 378:30-a? So the drafters added this third and final sentence: “All costs of construction work in progress, including, but not limited to, any costs associated with constructing, owning, maintaining or financing construction work in progress, shall not be included in a utility’s rate base nor be allowed as an expense for rate making purposes until, and not before, said construction project is actually providing service to consumers.”

And there you have it. Governor Gallen and his allies in the General Court wanted it to be so impeccably, transparently, irrefutably clear that no construction work in progress can creep into the rates of a New Hampshire utility that they drafted a statute making the exact same point three times, in a trio of cascading sentences.

But it doesn’t require three sentences to explain why they found this so necessary. It takes just a word: Seabrook.

By 1979, PSNH’s quest to build the Seabrook nuclear power plant was already in epic failure mode. As lead owner, PSNH originally held a 50 percent interest in the facility, which was supposed to include two reactor units. Eventually, PSNH’s interest was reduced to 35 percent, only one unit was finished, and the facility’s construction costs soared to nearly $7 billion. Completed in 1986, Seabrook did not actually go on line until 1990.

Before the passage of the anti-CWIP statute, the PUC had ruled PSNH could include the carrying costs of this construction project in its rates – not just in spite of the delays and cost overruns but, in a sense, because of them. A 35 percent share of a $7 billion facility is a potentially crushing burden if there is no revenue associated with this investment for year after year after year.

Eventually, it came time for the New Hampshire Supreme Court to rule on PSNH’s challenge to the constitutionality of the anti-CWIP statute. “Essentially, the company seeks a bailout,” said the Court, ruling that neither the U.S. Constitution nor the New Hampshire Constitution require any such thing.

The Court issued its opinion on January 26, 1988. Two days later, PSNH sought protection from its creditors in federal bankruptcy court. Seabrook investments would later also drive the New Hampshire Electric Cooperative into bankruptcy.

Forty years later, ironies abound.

Seabrook Station, now the property of the Florida-based utility and generation conglomerate NextEra, continues to chug away and is producing some of the cheapest power in New England. PSNH, now doing business as Eversource after bankruptcy reorganization and two ownership changes, is strictly a poles-and-wires operation; it is seeking an $82 million rate increase (to be paid for in part by $12 million in annual tax-reform savings). The company’s news release about the impending rate case brags of $1 billion in new investments over the past decade.

We ratepayer advocates are still trying to keep utilities from including in rates all costs that do not have a direct connection to the service the utilities actually provide. In the parlance of utility law, this concept is known as “used and useful.” Anything, no matter how virtuous or desirable, that is not actually used and useful in the provision of utility service does not belong in rates.

Regrettably, this truth is apparently not self-evident. Only last year, the New Hampshire Supreme Court refused to apply the “used and useful” principle to PSNH’s plan to put a big new natural gas pipeline in electric distribution rates, even though a poles-and-wires company doesn’t need any natural gas. Fortunately, the pipeline scheme appears to have gone dormant.

Not so with the construction of two new reactors at the Vogtle nuclear plant in Georgia, where utilities are still vertically integrated and thus still own generation. Units 3 and 4 at Vogtle are five years behind schedule, cost overruns have doubled the bill to $28 billion, and two years ago the debacle drove Westinghouse Electric (the big on-site contractor) into bankruptcy.

Georgia is not New Hampshire. In 2009, our neighbors to the south adopted the Georgia Nuclear Energy Financing Act, whose purpose is to put the construction costs associated with Vogtle units 3 and 4 straight into rates no matter how long the project takes to complete. Call it an anti-anti-CWIP statute.

Imagine if Chevrolet decided to jack up the price of a Silverado pickup by a third to cover the cost of a new factory to be opened a decade from now. The competition would drive Chevrolet right out of business after such a move – and regulated rates are supposed to subject monopolies like PSNH to the same kind of discipline.

Hugh Gallen understood this. Maybe it’s no coincidence he was a Chevy dealer in Littleton before he became governor.