By PAULA TRACY, InDepthNH.org

DIXVILLE – In the shadow of Dixville Peak, people have lived and hunted for thousands of years. The first Native Americans farmed and hunted the area. They included people of the Abenaki tribes whose population by the 1800s had been decimated by disease, war and migration.

Of those Abenaki who remained in New Hampshire, one was Mary Titus Hodge, the maternal great-grandmother of Neil Tillotson, the inventor, millionaire and North Country native, who bought the Balsams Grand Resort hotel in 1954.

Mary was a full-blooded Abenaki, according to Susan Zizza’s history of Dixville, Colebrook, Columbia, and Stewartstown, which was published in 2013. Mary and her husband David settled west of Dixville Notch.

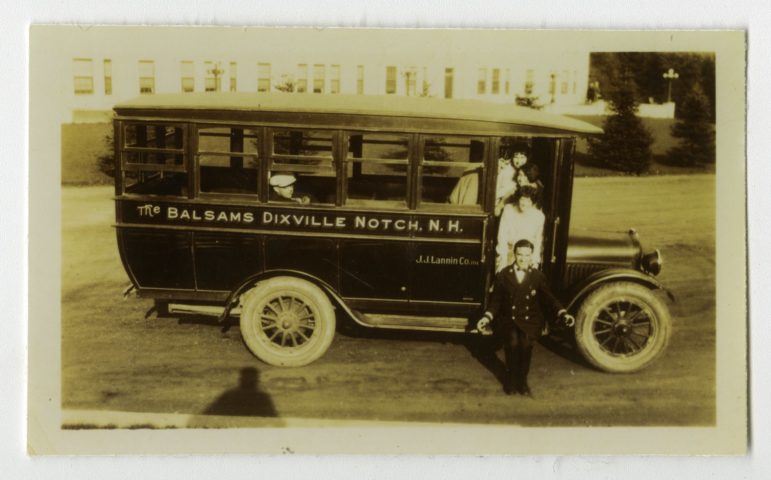

Courtesy of the Museum of the White Mountains, Barba Collection

Neil Tillotson grew up in Beecher Falls, Vt., and became a man of “unbridled curiosity about everything and went to work until the day he died,” on Oct. 17, 2001, just before his 103rd birthday, said his son, Tom Tillotson. He was also a man who couldn’t comprehend the concept of leisure travel, hardly ever vacationed himself, yet owned what was once one of the finest luxury hotels anywhere.

The younger Tillotson, one of the few remaining residents of Dixville, said his father always wanted to own land in the North Country, partly because of his great-grandmother. Tom Tillotson said Mary Titus Hodge was “always fearful she had no right to be there” living in New Hampshire because of her Native American heritage.

Neil Tillotson kept in touch with a well-known local judge from his home in Beecher Falls. Eventually, a property came on the market that he was interested in. But more about that later.

Early Beginnings

The Balsams first opened as a hotel just after the Civil War as the Dix House, according to Steve Barba, who worked for 47 years at the resort and became a managing partner.

It was first a 25-room summer inn established by George Parsons, Barba said.

According to historical documents kept by the Balsams, Parsons named his inn after the original grant recipient, Col. Timothy Dix Jr., a patriot who fought during the American Revolution. He received 29,000 acres from the Legislature in 1805.

Dix bought “Township Number 2” for nine payments of $500 each, with the proviso that he build a road and settle a community there, said Barba.

Dix died during the War of 1812, and famous New Hampshire son Daniel Webster, Dix’s lawyer, managed the property and the wilderness for the family.

Barba said Webster didn’t attempt to build the grist mill or the church that Dix had promised the legislature.

Webster, who had been a congressman from New Hampshire and a noted Supreme Court litigator, got into a row of sorts with then-Gov. William Plumer over Dartmouth College, Barba said. It resulted in Webster leaving for Massachusetts and abandoning the notch property and becoming a U.S. senator from the Bay State.

Eventually, the road was built, a hotel was established, and it catered to summer guests who would come for months at a time to get away from the heat and hubbub of an industrial world.

After Parsons’ death in the 1890s, the property was purchased by Henry S. Hale, a Philadelphia inventor, industrialist and regular guest at the hotel each summer.

He renamed the property The Balsams for its fragrant conifers which encircle the notch.

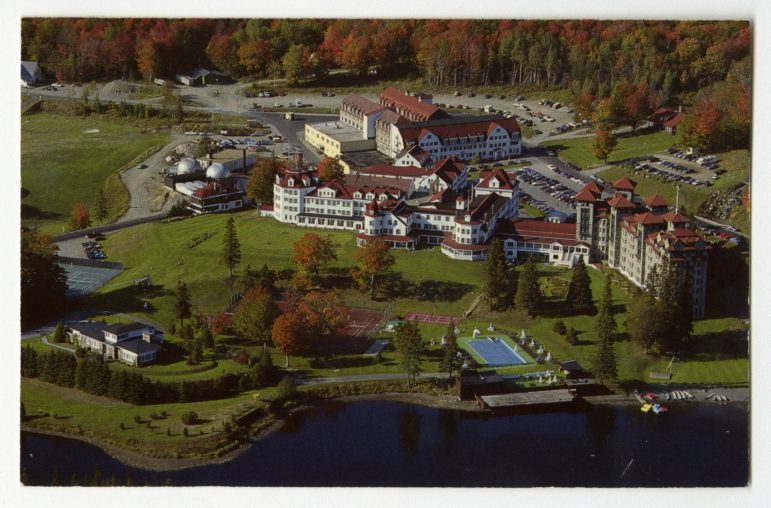

During the time Hale owned it from 1895 to 1922, the hotel and surrounding features expanded with the creation of multiple lakes, a canal system for drinking water, and the famous Panorama Golf Course designed by legendary golf course designer Donald J. Ross in 1912, according to the Balsams website.

The Hampshire House, finished in 1918, brought the Balsams into a new era, transforming the property into a 400-room grand resort. Unfortunately, Hale’s business investments tanked soon after, and in 1922 he was forced to sell the hotel at auction, according to the Balsams’ website.

This resulted in a new owner, J.J. Lannin, owner of the Boston Red Sox. Frank Doudera was the next owner from 1927 to 1941. It was during his ownership in 1929 that heavy spring rains broke the dam on Lake Gloriette washing out the main road and 72 buildings in downtown Colebrook. No lives were lost.

The times just prior to World War II were not accommodating to destination resorts, many of which, including the Balsams, saw a decline in the number of guests. After 1941, two owners tried to make a go of it, resulting in the property coming up for auction in the 1950s.

The Tillotson Era

Steve Barba, who now lives in Rhode Island, worked at the resort from 1959 to 2006, first as a golf caddy after attending caddy camp and ended his career there as president and a managing partner of the hotel.

Barba’s parents met at the Needham, Mass., rubber factory owned by the Tillotson family.

Neil Tillotson made his fortune developing an economical process for making latex balloons, and his company later invented a process and machinery for making latex exam gloves that fit either hand.

As a boy, Barba was introduced to the boss’s resort. He fell in love with the place.

Barba said Tillotson was not much for leisure travel and never took a real vacation. In fact, Tillotson considered those who did to be idle, self-indulgent fools, according to Barba. “He didn’t understand it at all,” Barba said.

Tom Tillotson agreed. He noted that his father also never liked the fact that the Balsams was protected by a gate. At the time, Neil lived in Beecher Falls, Vt.

“The place was off-limits to local people,” Tom Tillotson said. “He felt that it was wrong.”

Barba said the elder Tillotson was always interested in acquiring land in the North Country, and he had a sentimentality toward his great-grandmother, Mary Titus Hodge, a homesteader who lived in the area and felt like an outsider.

Neil Tillotson would keep in touch with Colebrook attorney Fred Harrigan, father of North Country writer John Harrigan. Fred Harrigan called Neil Tillotson one day about an upcoming auction of the Balsams and its thousands of acres of woodland.

“He was not interested in the hotel,” Barba said, but the vast tracts of timber were attractive to him. Otherwise, he would not have attended the auction.

Neil Tillotson saw the hotel as “an inconvenience,” Barba said. He had no interest in being a hotelier.

Something clicked

But at that auction, something clicked in Tillotson, and he acted out of “a fit of middle-aged sentimentality” for his great-grandmother Mary, Barba said. It was also fortuitous that in the auction crowd that day was former owner Frank Doudera, who assured Tillotson that if he bought the hotel, Doudera would run it for him and he did for many years.

Tom Tillotson said it was also in his father’s mind to find a place to move his rubber factory north from Massachusetts. The area around Needham was growing quickly with the development of Route 128, and the younger Tillotson said his father felt the rubber factory would be squeezed out from the expensive, developing region near Boston.

In the 1960s, Neil Tillotson moved his rubber factory to the Dixville property adjacent to the hotel. At the time, the Balsams was a successful resort, but open only in summer.

Tom Tillotson said the old model of a grand hotel in the White Mountains was giving way to a trend with travelers who had different tastes and shorter stays in mind.

The factory was successfully making balloons as well as supplying heat for the hotel. That would change things since it would allow the hotel to remain open during the winter months.

Rather than having hotel staff imported from Florida for the summer, the hotel could hire year-round employees, Barba said.

That was a game changer.

Until then, summer staff would work at the Balsams in the summer, then head south during the colder months to work at the resorts among the palm trees in Florida, Barba said, but staying open in the winter would open up year-round employment opportunities for local people.

Having year-round staff helped profitability, hospitality and community support, Barba said.

These were considered good jobs with good pay and year-round reliability. Several hundred people, mostly from Colebrook, had jobs beginning in the 1970s until the grand resort closed in 2011.

To make these good jobs possible, what the Balsams needed was more winter amenities to draw visitors. Neil Tillotson built a small ski area, naming it the Wilderness Ski Area, which was open to hotel guests as well as to the public.

“Mr. Tillotson loved the fact that the local residents were working in the hotel,” rather than the migrant Florida crowd.

It signaled a change in Tillotson and his attitude toward the hotel, Barba said.

Tom Tillotson said he believes his father warmed to the hotel, not because it was solvent, but because its staff was comprised of local people.

Barba said he sensed Tillotson was proud of the hotel and proud to know that the maître d handling meal service was a woman who lived down the road.

One of Barba’s proudest moments was seeing Neil and Louise Tillotson in the dining room, enjoying the hotel and property they had never stepped foot in before.

Larger scale needed

Last month, in addressing a House committee on legislation related to the redevelopment of the Balsams, Tom Tillotson told lawmakers that part of the hotel’s downfall was the lack of scale regarding the ski area and its ability to support the winter operation.

Tillotson said his father was not a ski area developer, and they didn’t know that the back side of the ski resort held a treasure trove of terrain, a protected bowl that gets loads of snow blown into it each winter.

When ski developer Les Otten came to look at the ski area and the resort at the request of then-owners Dan Hebert and Dan Dagesse in 2013, he discovered vast terrain on the back side forming a natural bowl high in elevation with plenty of natural snowfall.

It was like striking gold for Otten, who later bought Dagesse’s share for an undisclosed amount. Otten said he began picturing in his mind what he believes could be the largest ski area in New England.

Such a scale, Otten maintains, would be enough to support a successful destination, year-round resort with a 450-bed base.

Changing with the times

The advent of locals working year-round at the hotel was crucial to its success for 30 years, and Barba said he does not believe it could have lasted as long if it did were it not for the homey touch.

The normal coat-and-tie requirements of the dining room relaxed a bit in the winter, and hotel guests unprepared for the deep snow and cold would often be given mittens to borrow from the staff.

Friendships developed.

This was “a huge difference in the experience” from what these people were used to, Barba said, and there became more of an integration of cultures, as friendships among staff and guests grew.

It contributed to return guest numbers that were “extraordinarily high,” for the industry, Barba said.

“They got a bit of a local experience because it was very homey and very informal” in winter, he said.

Skiers wanted buffets, not white table linen service.

The culinary staff maintained its haute cuisine standards nonetheless, providing an exquisite buffet that helped create a niche in the ever-changing hotel market, Barba said.

Tillotson gave Barba and a group of department heads at the hotel roles as managing partners, and they did a fairly good job of keeping it break-even, Tom Tillotson said.

Also helping was the fact that the food was fantastic at the hotel.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the cooking school became internationally recognized, and the hotel became an epicurean destination.

End of an era

Neil Tillotson died in 2001, weeks before his 103rd birthday. Delaware North, a huge hospitality company, came in to take over operations, but they failed massively, Tom Tillotson said, in part because costs were rising with the closing of the balloon factory, and Delaware North was accustomed to a different sort of drive-by business.

Tom Tillotson said there is simply no drive-by business in Dixville.

“The economic situation was fragile,” the younger Tillotson said.

In 2006, Barba said, it became evident that the hotel could not continue at the same scale and the trust required that it be liquidated and transitioned in ownership.

In December 2011, two North Country businessmen, Hebert and Dagesse, purchased the hotel and its property for $2.3 million and began to look at ways to restore it.

After holding an auction of the hotel’s furniture and other items, they reached out to Otten, who lives nearby in Bethel, Maine. Otten had extensive experience developing ski resorts across the country, including Sunday River in Newry, Maine.

And the rest is history in the making as Otten looks to proposed legislation, House Bill 540, to help move financing of the $173 million redevelopment project forward.

Sponsor Rep. Edith Tucker, D-Randolph, said the legislation is scheduled to be heard by the Senate Commerce Committee at 1 p.m. on April 9 at the State House in Concord. The bill, which would allow unincorporated places to create tax assessment districts for redevelopment, has already passed the House by a wide margin.