Sign up for our free newsletter here.

By PAULA TRACY, InDepthNH.org

CONCORD – Calling the Coakley Landfill in North Hampton a “toxic soup,” state Rep. Renny Cushing, D-Hampton, on Tuesday asked fellow lawmakers to take action to clean it up now.

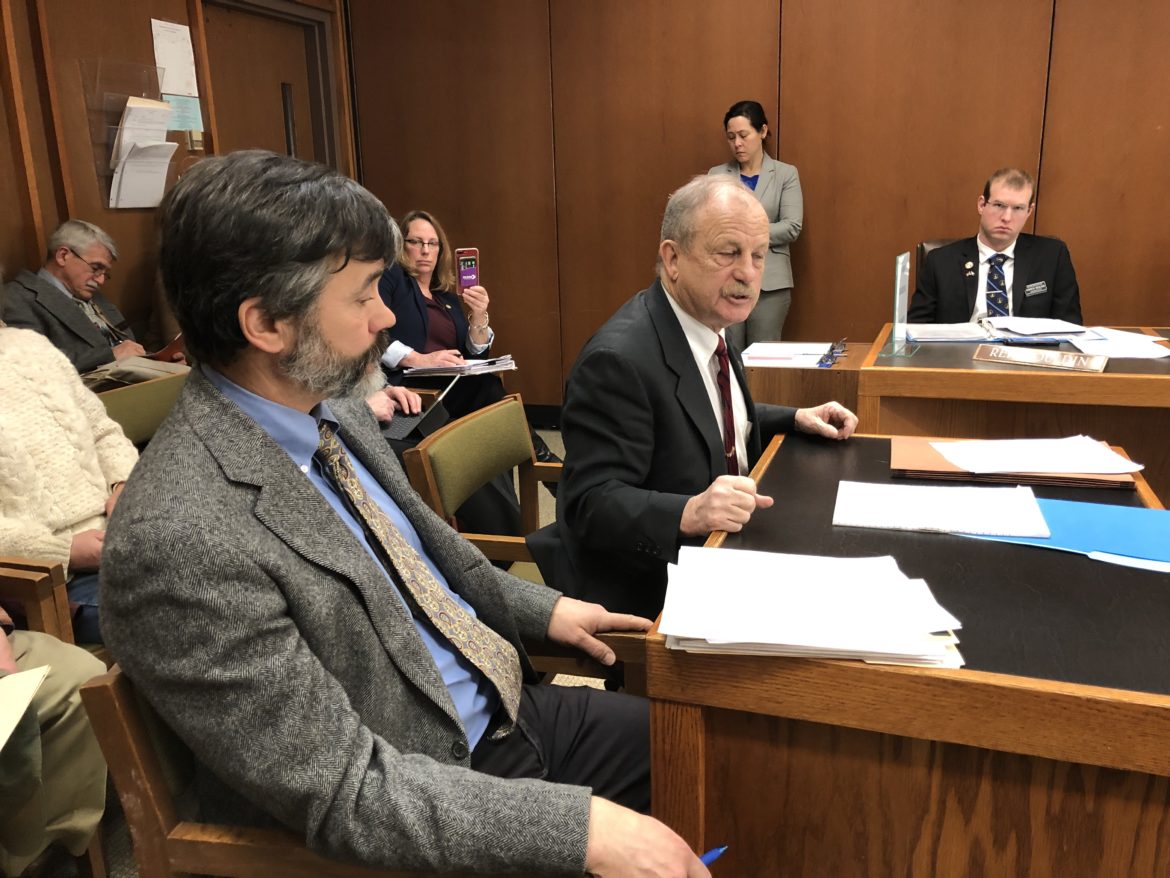

But speaking to members of the House Environment and Agriculture Committee, Robert Sullivan, a lawyer for the city of Portsmouth, which is part of the Coakley Landfill Group, said there is no imminent threat to public health as the bill describes.

The state, by taking unilateral action to control the Superfund site would violate contracts with CLG and the federal government, Sullivan said.

House Bill 494 orders the Department of Environmental Services to “pursue a remedy regarding the removal or containment of certain contaminants” on the 27-acre property. It would require the Coakley Landfill Group to pay for it, the cost of which was not provided.

It would be an “unbelievable amount of money,” said Sullivan, declining to estimate a dollar amount to remove or contain the waste there.

The Department of Environmental Services also opposed the bill noting the federal Environmental Protection Agency is in control of the Superfund site.

But Mindi Mesmer, a former state representative and congressional candidate, who began her political career looking into the health concerns posed by the Coakley Landfill, said this precautionary approach should be taken to prevent cancers.

When the Coakley Landfill Group is “pushed, things finally begin to happen,” Messmer said.

She agreed with state Rep. David Meuse, D-Portsmouth, who said Coakley is being handled as a financial problem rather than the “imminent risk” to health that it presents.

Coakley began as a bedrock gravel pit on the highest point in the Seacoast in the 1970s.

The landfill is near the headwaters of Berrys Brook, which is located in North Hampton at the edge of Greenland and Rye.

From 1972 until 1985, it was used as a municipal landfill. The dumping of toxic and incinerator waste was also allowed along with municipal waste from area communities.

About 63 percent of the Coakley Landfill Group is represented by municipalities, along with about 25 haulers and generators of waste, which represent the other 37 percent.

It was capped in 1998.

Cancer cluster

Concern about potential groundwater contamination surfaced in the 1990s. In 2016, a state report revealed a small cluster of pediatric cancer cases in the area.

While members of the Coakley Landfill Group said there is no proof of carcinogens coming from the landfill property, the bill asks that it be considered an “imminent hazard due to substantiated and real threats to public and private drinking water in the towns of Hampton, North Hampton, Rye, and Greenland, and the surface water bodies that flow through all seacoast towns, including but not limited to Hampton, North Hampton, Rye, Greenland, and Portsmouth.”

Cushing, who sponsored the bill, said it shocked him to learn that there was no liner for the landfill.

“It’s threatening the drinking water of the people of the New Hampshire Seacoast and the surface water,” Cushing stressed.

A member of the committee, state Rep. Peter Bixby, D-Dover, asked where the funding would come from.

“The polluters,” Cushing said, referring to the Coakley Landfill Group.

Rep. Meuse said Coakley sits there “like a ticking time bomb.”

Meuse said he became aware of the problem because of comprehensive news reporting on the subject in his area.

“I think it is really important for people like us to take action,” Meuse told the committee. “What it comes down to is as a legislature, we have a responsibility to act and this bill ensures that we take that seriously.”

The bill includes correspondence from the DES to the Coakley Landfill Group, which states that tests exceed standard levels for carcinogens. The report confirms that the concentration of 1,4-dioxane exceeds the recently revised Ambient Groundwater Quality Standard (AGQS) of 0.32 ppb.

It ordered “corrective action.”

“The long-term solution is to get it out of there,” Cushing said.

Environmental Services

Mike Wimsatt, director of the waste management division of the Department of Environmental Services, said the department opposes the bill as written.

To declare an imminent risk is a “high bar” that this case does not reach, Wimsatt said.

He also explained that the federal government is in control of the matter.

PFAS, a chemical now found at Coakley, are much more persistent and don’t degrade well, Wimsatt conceded. PFAS has been linked to two cancers, but it is still considered suspect in others, although testing continues.

Wimsatt said the agency is proposing new lower standards for PFAS this year and the site is being constantly tested as is the nearby brook.

“DES shares the concerns of the sponsors,” Wimsatt said. “We have been working very hard with the (Environmental Protection Agency),” Wimsatt said.

Because it is one of the state’s 22 Superfund sites, “they are in the driver’s seat. We feel we have a responsibility for oversight, but at the end of the day…that’s EPA’s call,” he said.

Wimsatt continued: “We do believe the migration from Berrys Brook is unacceptable.

“Having said that we are not in a position to compel it,” because the state does not have standards for PFAS yet, Wimsatt said.

There are signs at Berrys Brook that notify visitors of the problem and warns them not to drink the water or eat the fish.

Rep. Bixby asked if there is another alternative to get something done.

Wimsatt said there is still testing going on.

“It does take time and it is frustrating,” Wimsatt said. “We don’t believe we have the data.”

Coakley Landfill Group

Attorney Sullivan, representing the city of Portsmouth, and Peter Britz with Coakley Landfill Group, spoke together in opposition to the bill.

Sullivan said the Coakley Landfill site is “a very complicated, very expensive, very serious problem.”

“The (CLG) group would say to you now that number one, there is no imminent hazard at the site. No one is drinking water unsafe because of the Coakley landfill. There are issues that require monitoring and when remedial action is required, it has been done virtually immediately,” Sullivan said.

Number two, he said, requiring the DES to do something would be breaking a contract.

During the 1990s when the problems first began to surface, the responsible parties, state and federal government entered into agreements to deal with them, he said.

That resulted in two consent decrees, “really contracts” signed by all parties including the state. It provided structure to move forward, Sullivan said.

“If you tell DES to do anything other than what is in those contracts, it will breach the contracts,” Sullivan said.

“The U.S. government has kept their word, the parties have kept their word, we would hope the state would continue to keep its word,” Sullivan said.

A copy of the DES history of the Coakley site and its findings is located here https://www.des.nh.gov/organization/divisions/waste/hwrb/fss/superfund/summaries/documents/coakley.pdf

New Hampshire has 22 Superfund sites. Here’s a link to where they are https://www.epa.gov/nh/list-superfund-npl-sites-new-hampshire

InDepthNH.org is New Hampshire’s only statewide, nonprofit daily news outlet.