Distant Dome is co-published by Manchester Ink Link and InDepthNH.org

By GARRY RAYNO, Distant Dome

This is the political season and politicians love to tout New Hampshire’s growing economy but are not as likely to say the expanding prosperity is not shared evenly throughout the state.

This is the political season and politicians love to tout New Hampshire’s growing economy but are not as likely to say the expanding prosperity is not shared evenly throughout the state.

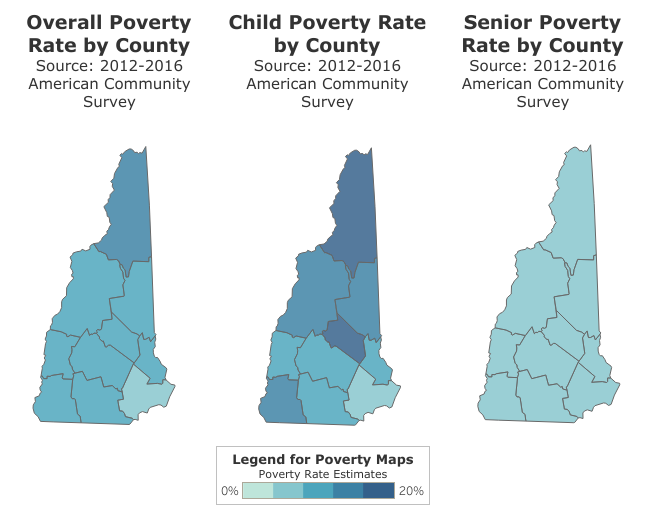

The economic prosperity is centered mostly in the southeast corner of the state while the more rural northern and western areas have not seen benefits.

While the disparity is evident region to region, a The issue brief, “Measuring New Hampshire’s Municipalities: Economic Disparities and Fiscal Capacities,” uses US Census Bureau data, enrollment in social service programs such as Food Stamps and Medicaid, communities’ property values, and income data to determine communities’ abilities to raise revenue to address local needs. Prior studies have often focused on public education costs and the disparities between property rich and property poor communities and how that impacts educational opportunities for students. While public education costs are more than all other local and county services combined, the economic disparities also impact the quantity and quality of local services. All services The NHFPI study looks at a community’s ability to raise the money needed to provide all local services including schools, highways, recreation and libraries. “In general, municipal fiscal capacity and local needs for services can range from having high capacity to raise funds and relatively low-cost needs, to having low capacity to raise funds and relatively high-cost needs,” said the report’s authors Julia Vieira, Research Intern, with Phil Sletten, Policy Analyst. “This Issue Brief explores the implications that different demographic and socioeconomic characteristics can have in terms of municipal fiscal capacity and local needs across the state.” They also note both Hillsborough County and Merrimack County are indicative of the differences among major urban centers, adjacent suburban communities and smaller cities and rural towns. For example they note, southwestern Grafton County — Hanover, Lyme — includes certain high-income areas while the rest of the county has lower incomes and higher social service program use. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the study is the look at the per capita property wealth of communities. Those with high values have little trouble raising the necessary money to pay for local services while maintaining low property tax rates, while poor property value communities have high property tax rates to raise the money they need. Top Scale The communities at the top of the scale either border a significant water body or have a high percentage of second homes like Moultonborough or Rye, while those on the lower end have experienced population and industry loss such as Berlin and Claremont. Two communities stand out among the most wealthy: Newington and Waterville Valley, which both have property value of more than $1.3 million per resident. Newington has $1.376 million in property value per resident, while Waterville Valley has $1.33 million per resident. The next highest community is New Castle with a little less than $750,000 per resident followed by Moultonborough, Monroe, Lincoln, Jackson, Hebron, Carroll and Tuftonboro. The community with the least property value per resident is Berlin $39,816, followed by Greenfield at $46,359, and then Northumberland, Claremont, Troy, Charlestown, Boscawen, Plymouth, Winchester and Pittsfield. Among those 20 communities, New Castle has the lowest tax rate of $5.85 per $1,000 of assessed valuation, while Claremont is highest at $42.66 per $1,000. Five groups The authors break communities into five groups: The top tier includes Waterville Valley, New Castle and Moultonborough which are either located along a significant water body like lakes Newfound, Sunapee, and Winnipesaukee, or near the White Mountains, or have a large number of second homes and few year-round residents. The second group includes communities with large commercial or industrial property with few resident such as Newington, Portsmouth and Seabrook. The third group is comprised of large cities such as Manchester, Nashua or Concord with some of the highest total property values but not per capita value. The fourth group includes communities like Bedford and Bow which are relatively wealthy with above average property values but mostly residential and without a large commercial or industrial base. And the final group struggles the most to raise money for services with low total property value with low to mid-sized populations such as cities Claremont and Berlin, and towns Allenstown, Lisbon, Troy, and Pittsfield. The authors note the great disparity in property tax rates among Granite State communities and how that impacts the services a community is able to provide. “Municipalities with lower populations may face a higher cost per capita to establish and maintain public infrastructure at the local level. This could have a great impact on access to services and potential municipal investments. Municipalities with smaller populations and property tax bases often struggle to raise funds to finance needed infrastructure, as each resident must face higher financial cost per dollar of property value to fund investments. Coupling smaller communities’ limited fiscal capacity with their higher incidence of aging population, inequities in access to services and economic opportunity may emerge across the state’s municipalities,” the authors write. Income and age The researchers also found that the relative property wealth of a community corresponds with a communities’ medium income, and the average age of a resident. While urban areas like Portsmouth, Manchester and Nashua tend to have a younger average age — with the youngest being in the college towns of Durham, Keene and Plymouth — many rural property poor communities have a higher average age along with retirement communities like New London, Grantham, the Lakes Region and small towns in the White Mountains like Easton and Franconia. What does it all mean? “In general, municipalities with greater fiscal capacities in the state have more resources to provide services and infrastructure and a larger population falling within traditional working ages,” the authors conclude. “Middle- and high-income families are often attracted to municipalities that can offer good educational and recreational services as well, and may be more likely to have the means to relocate to those municipalities.” And they say communities with recreational and natural amenities also attract wealthier retirees, second-homeowners and tourists. “Unfortunately, the most fiscally-challenged communities in New Hampshire can face both proportionally high costs and low revenue capacity,” Vieira and Sletten write. “Those are the communities facing population declines, a lack of job opportunities, and high poverty rates, along with fewer taxable resources to enable government investments and generally higher property tax rates, which may discourage new or continued business investment or families from moving into those communities.” State government could help to alleviate some of the disparities by targeting and expanding anti-poverty programs, instituting policies to ameliorate the impacts of declining populations, and fostering local economic development programs, they contend. Essentially, communities that have will continue to grow and those that don’t will need state help or they will continue their downward spirals. That is not all. The authors had another warning to all. “Superseding most municipal disparities, every community in New Hampshire will likely face challenges in providing social and health care services to the growing senior population, with significant fiscal implications for the future.” In other words, New Hampshire is growing old in place and the state needs to determine how seniors citizens will fair in the future. Many communities 20 years ago encouraged over age 55 developments believing they would increase the tax base without putting children in school systems. Now the student population is declining, fewer students attend state colleges because of the high tuitions and many never return. But seniors are growing older here creating new issues that will need to be addressed. A short-term solution to skyrocketing property taxes created a much bigger problem the state needs to address in the next decade. It’s funny how that happens. Garry Rayno may be reached at garry.rayno@yahoo.com Distant Dome by veteran journalist Garry Rayno explores a broader perspective on the State House and state happenings. Over his three-decade career, Rayno covered the NH State House for the New Hampshire Union Leader and Foster’s Daily Democrat. During his career, his coverage spanned the news spectrum, from local planning, school and select boards, to national issues such as electric industry deregulation and Presidential primaries. Rayno lives with his wife Carolyn in New London. Garry Rayno[/caption]

Garry Rayno[/caption]