By Michael Davidow, Radio Free New Hampshire

No, I won’t write about Hillary Clinton’s star turn at the Grammy Awards this past month, even though her burnishing her celebrity credentials at this late date is upsetting, to say the least.

Michael Davidow of Manchester

No, let’s just say that the Grammy team did us a favor, giving us that homeopathic dose of her hubris, thereby helping us prepare for the inevitable: her appearance at the Democratic National Convention in 2020, when she will stoop to accept her party’s applause, cause the American populace to wonder if it has been sucked into some sick sort of time warp, and otherwise do her best to poison with her presence, whoever has been nominated in her stead.

No, I won’t do that. Because this is my Valentine’s Day column, so I’ll write about Woody Allen instead.

Woody has been in the news again, because his step-daughter has renewed her accusation of his molesting her when she was young. He has always denied that, and he still does. I don’t have a dog in that fight. But it’s interesting, because in this me-too moment, actors and actresses are now shying away from his films, and critics are now asking whether we are even allowed to watch his work anymore, given that he has been labeled (and — because the court of public opinion has little truck with due process– is now assumed to be) a sex offender.

In that sense, the Woody question is part of that larger dilemma, raised a little while ago, about the propriety of maintaining statues of Confederate war heroes and other known racists (like Theodore Roosevelt) on public land. Knowing what we know about these people, this argument goes, how can we still approve of them and their works?

I know something about this, because as a Jew, I live surrounded by celebrations of people who were known and often vicious anti-Semites. That would be pretty much every non-Jewish person in the western world, since Constantine made Christianity the Roman state religion ca. 300 AD, up to the past few decades. Jews aren’t typically given the option of editing their surroundings, though, nor of destroying monuments to these people. Minnesota is strangely silent on renaming the city of St. Paul, and England stubbornly fond of Shakespeare.

Over the years, then, I have made my peace with the notion that humans are complicated; that their worst moments should not be made to stand for their lives. While I am unimpressed by what Henry Ford had to say about Jews, I nevertheless accept his contribution to the automobile industry, and I do not cringe when I see his cars on the road.

There are limits, of course. I have friends who majored in philosophy in college, and they are strangely tolerant of Martin Heidegger, who made his bed with the Nazis for years. I can’t listen to any philosopher, under any circumstances, whose philosophy allowed him to do that. And I can therefore understand why many African-Americans cannot abide having statues of people like Nathan Bedford Forrest lying around, whose main non-Civil War claim to fame is his founding of the Ku Klux Klan.

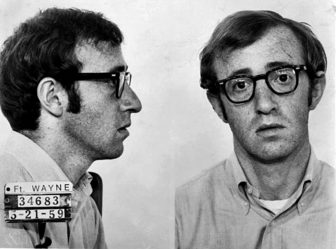

Wikimedia Commons

Woody Allen in 1969 photo from movie Take The Money.

Which leads me back to Woody Allen. Because the problem with his movies is not that he once allegedly committed a crime. The problem with his movies is that his movies are lousy. Repetitive, dull, self-indulgent. And they are lousy because he is a consistently shallow person, putting all escapades with his step-children aside.

When he married one of his former wife’s adopted children, a very young woman he had known since she was a girl, he explained himself by saying, “the heart wants what the heart wants.” I suppose that’s true, if you’re ten years old, and you have no moral fiber, even for a ten-year-old. But for most of us, that’s not true. And if your movies reflect that belief, over and over, then you are making movies with a sickly pallor.

Like every other part of your body, your heart wants what’s good for it. Sometimes, that can also be what it wants right away. But not always, and perhaps not even often. Infatuations come and go. Desires get met, only to feel stale.

If you have been lucky enough to have found a partner, though, and to have built a home with that person, and to have raised a family with him or her, then you will have learned that the love that grows over time, that comes to sustain you, and that comes to define the parameters of your emotional life, is hardly the stuff of a momentary whim. It is the stuff of discipline, and patience, and time. It is complicated, like people are complicated. And if Woody Allen made movies about that, I would watch them in spite of his crimes. But he doesn’t, so I don’t.

See? I told you. It’s a Valentine’s Day column.

Michael Davidow is a lawyer in Nashua. He is the author of Gate City, Split Thirty, and The Rocketdyne Commission, three novels about politics and advertising which, taken together, form The Henry Bell Project. His books are available on Amazon.