Please sign up for InDepthNH.org’s free weekly newsletter published every Friday

By Michael McCord,

InDepthNH.org

Among the many environmental byproducts of global climate change, the lesser known process called ocean acidification is posing an immediate threat the New England shellfish industry, experts say.

As excess carbon dioxide is absorbed into the oceans combined with freshwater runoff into coast waters, it is starting to have profound effects on marine life, from oysters to tiny snails at the base of the food chain.

In New Hampshire, Sen. David Watters (D-Dover), oversaw the passage of a bipartisan 2016 bill that established The New Hampshire Coastal Marine Natural Resources and Environment Commission which began meeting earlier this year.

NH State Sen. David Watters, D-Dover

“The Commission has received in-depth briefings surrounding the causes of ocean acidification, through the deposition of C02 from the atmosphere, and the effects on water chemistry,” Watters said about commission meetings. In particular, he emphasized the impact of ocean acidification on the complex ecosystems in the Gulf of Maine and the Great Bay estuary.

“We learned that the effects are exacerbated and accelerated in colder and fresher waters, thus the greater impact on the Great Bay and coastal waters, as well as the loss of buffering in New England soils due to acid rain, which means more acidic water is running off the land into rivers and estuaries,” Watters explained.

“We learned about the impact of acidification on the entire food chain, and particularly on shellfish, such as oysters, of particular concern to aquaculture in the Great Bay, and to mussels, crabs, and eventually lobsters. It also is related to water quality, since oysters are needed to filter the water in the Great Bay, and the presence of nutrients makes it more difficult for water to buffer and reduce acidification.”

It was three decades ago when scientists and policy makers tackled acid rain’s impact on rivers, streams, lakes and forests in the United States northeast (caused by coal-burning power plants in the Midwest). Acid rain and ocean acidification are related but not the same.

Following the lead of Washington State, which more than a decade ago realized the extent of ocean acidification on its oyster population, Maine and New Hampshire have stepped up their scientific and legislative initiatives to raise awareness, document what’s happening and provide remedial solutions.

What is ocean acidification? Bärbel Hönisch, a biologist and oceanographer at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, has called it “the evil twin of global warming.” The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) offers this definition and what it means for the development of healthy shells for marine organisms like oysters and lobsters:

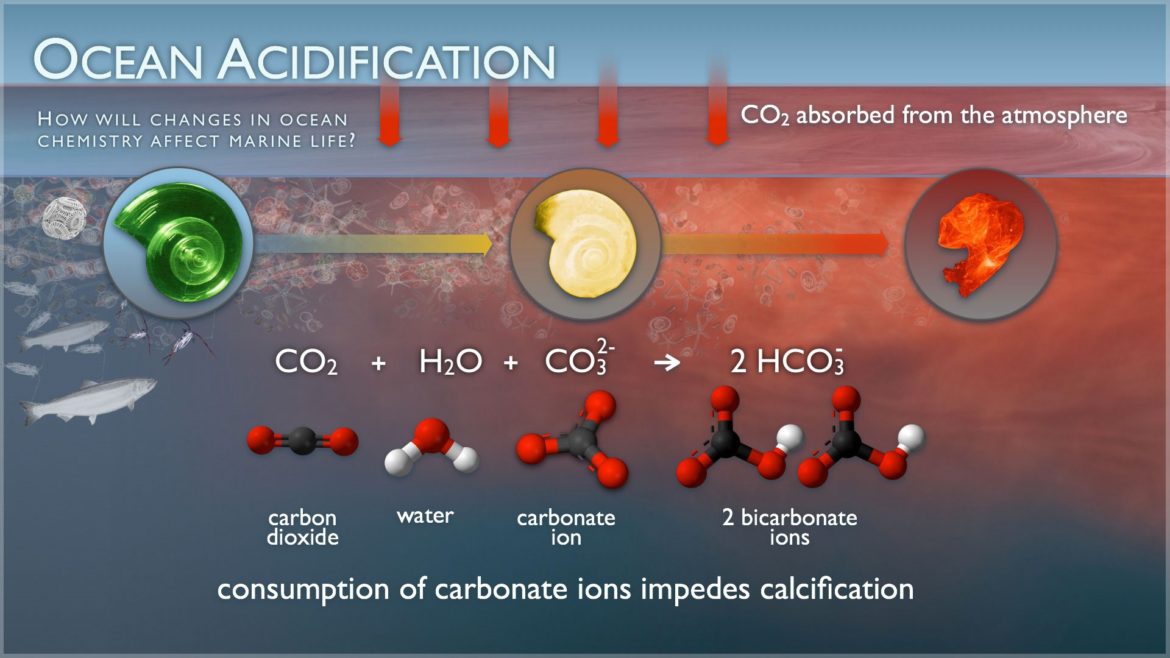

“When carbon dioxide (CO2) is absorbed by seawater, chemical reactions occur that reduce seawater pH, carbonate ion concentration, and saturation states of biologically important calcium carbonate minerals. These chemical reactions are termed ‘ocean acidification’ or ‘OA’ for short. Calcium carbonate minerals are the building blocks for the skeletons and shells of many marine organisms.

”In areas where most life now congregates in the ocean, the seawater is supersaturated with respect to calcium carbonate minerals. This means there are abundant building blocks for calcifying organisms to build their skeletons and shells. However, continued ocean acidification is causing many parts of the ocean to become undersaturated with these minerals, which is likely to affect the ability of some organisms to produce and maintain their shells.”

Overall, according to a recent article from the Smithsonian Institution, scientists believe that the oceans have become 30 percent more acidic over the past 200 years as oceans are estimated to soak up about 22 million tons of Co2 daily. The acidic increase is faster than any known change in ocean chemistry over the past 50 million years.

“When you read the literature, it made sense to those of us who study this that the impact of the industrial revolution would lead to a changing ocean chemistry,” said Joe Salisbury, a biogeochemical oceanographer and faculty member at the UNH Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space. “Our measurements in the field (on ocean acidity) showed very dynamic changes.”

But rising Co2 levels in ocean waters is but one factor. Salisbury was a member of the 2014-2015 Maine legislative-sanctioned commission to study “the existing and potential effects on species that are commercially harvested and grown along the Maine coast.” The January 2015 report (link here) highlighted the dynamic of land/freshwater sources impacting cold coastal seawater.

“While the global scale process of ocean acidification is fairly straightforward and well understood, other sources of acidification also affect Maine’s marine environment and in some cases can exacerbate the increases of acidity from atmospheric CO2…freshwater runoff and nutrient loading from onshore sources,” the report read.

“We are working with fishing industry,” said Salisbury who was part of a 34-day, 2015 NOAA-funded research voyage studying ocean acidification from Canada to Florida. “There is a billion dollars of product in the Gulf of Maine and aquaculture for oysters and other shell fish a real growth opportunity. It’s a good clean farming technique.”

To help these vulnerable industries, Salisbury created a “black box” that helps to monitor Co2 and other ocean water variables that come into hatcheries who can them adjust pH levels accordingly.

Salisbury said Maine has been a “real leader” on the east coast but everyone is catching up to and learning from the state of Washington. A serendipitous occurrence a decade ago off the coast of Washington – NOAA research scientists detected a major drop in pH levels (which leads to more acidity) at the same time that once-thriving oyster hatcheries had a dramatic decline in production – led to a legislative blue-ribbon commission, scientific experimentation and budgeted money dedicated to combating the problem (the 2012 study and recommendations can be found here).

Washington has also shared its lessons with the rest of coastal parts of the country facing similar challenges. “The process of getting the bill passed revealed how little people know about ocean acidification, despite the fact that it may be the greatest threat to our economy in the region, if, for example, we lose lobster and other high value fisheries,” David Watters said.

“I have been working on the issue for a few years, learning a great deal from Washington State Sen. Kevin Ranker, who is a national leader on the subject and has worked with the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators on it. He traveled here to meet with legislators and representatives from New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services and other agencies to discuss what is being done on the west coast.”

In addition to securing state funding to upgrade DES equipment to monitor pH levels, Watters hopes that the commission’s work will help educate the public.

“It may be that the connection to MS4, the new storm water regulations which have everyone’s attention in seacoast and Great Bay communities, may be an avenue for education on acidification. The increasing public awareness of oyster aquaculture in the Great Bay may also increase public concern about acidification,” he said.

These state initiatives come as the Trump administration, which continues to deny the existence and impact of global climate change, proposes to eliminate funding from Environmental Protection Agency budgets for estuary studies and that would decimate pH monitoring programs.

Watters believes there is no time to waste. “Our last meeting was with Bill Mook of the Maine Oyster Farm. His farm provides most of the seed oysters for the east coast and he is an industry leader in providing mitigation techniques and technology,” Watters said. (Mook has worked with closely with Joe Salisbury and has employed the “black box” at his farm.) “He has promoted great research into the impacts for he feels acidification is already in a crisis stage.”

For more information also visit the Northeast Coastal Acidification Network here.

The New Hampshire Coastal Marine Natural Resources and Environment Commission is tasked with:

Investigating, monitoring, and proposing prevention and mitigation strategies for emerging environmental threats in coastal and Great Bay waters, including but not limited to warming of waters, ocean acidification, sedimentation, and nutrient loading

Identifying gaps and recommending improvements in water quality monitoring, including monitoring pH and evaluating its impact on the impaired waters designation of water bodies

Recommending strategies for enhancing capacities for improving water quality

Examining the Blue Carbon credit program for sea grass promotion and oyster bed restoration