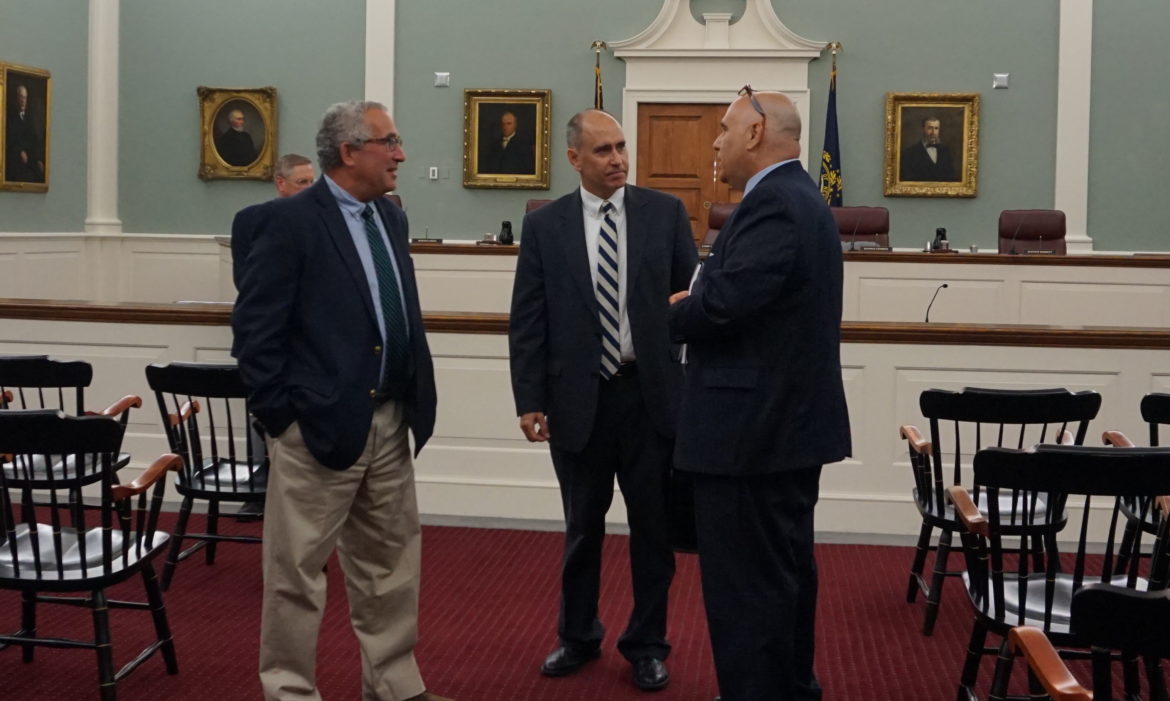

Nancy West photo

Assistant Attorney General Frank Fredericks argues the state’s position at the state Supreme Court on Thursday. Justice Robert Lynn is pictured on the bench. At right is Tom Reid.

CONCORD — Attorney Tom Reid argued on Thursday that the public has a right to the unedited documents Attorney General Joseph Foster relied on to temporarily remove Reid’s former boss, then-Rockingham County Attorney Jim Reams, from office in November of 2013.

At the state Supreme Court in Concord, Reid argued his appeal of Merrimack County Superior Court Judge Larry Smukler’s decision that allowed Foster to release only the heavily edited documents in the Reams’ investigation.

Smukler found Foster violated the state’s right-to-know law for taking too long to release the records, but ruled it wasn’t intentional. Many of the more than 7,000 pages were partially redacted or totally blacked out, Reid said.

“What’s not out (in public) is information that might have shown the attorney general misrepresented things or lied. These are all possible, but the public doesn’t have to take their word for it,” Reid told the justices.

This appeal is about the public’s right to know, he said. “This case is about democracy,” Reid told the justices.

Reid was Reams’ deputy county attorney and was also suspended on Nov. 6, 2013. When Reid resigned two months later, Foster issued a news release saying Reid had cooperated and was never a target in the probe. Reid now practices law in Concord.

“Fundamentally the right-to-know law provides that we as the public have the right to obtain the utmost information about what our government — in this case the Attorney General’s Office and the Rockingham County Attorney – are up to,” Reid said.

Assistant Attorney General Frank Fredericks told the court that the documents were appropriately redacted because they involved exemptions under the right-to-know law, specifically personnel matters and individual privacy rights.

Foster, a Democrat, filed a removal complaint against Reams, a Republican, on March 11, 2014. The complaint accused Reams of ethical violations, financial mismanagement, and gender discrimination.

No criminal charges were filed. Merrimack County Superior Court Judge Richard McNamara ordered Reams back to work the following month saying the attorney general didn’t have the authority to remove Reams from office. Reams retired in mid-June of 2014. He was to be paid his salary through the end of the year.

On Thursday, Justice Robert Lynn asked Reid if a new attorney general could decide to disclose the information that Foster had redacted.

Reid said: “I think the attorney general would have an obligation to release this information.”

“What the attorney general did was remove an elected official back in November 2013. For months no information was provided to the public,” Reid said. “What greater affront is there to the democratic process than to remove an elected official?”

Justice Carol Ann Conboy focused several questions on the fact that Judge Smukler relied on Foster’s characterizations as to why the documents were redacted.

“My concern here is the trial court never conducted an in-camera review of the documents,” Conboy said.

If a sexual harassment claim was made to the state Human Rights Commission, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or the Labor Department, the information contained in the complaint would become public, Reid said.

An internal investigation at the Rockingham County Attorney’s office was completed and the issues were resolved a year and a half before the attorney general’s investigation, Reid said.

When an attorney general starts an investigation, people would presumably understand their interviews may become part of a public proceeding and they may be asked to testify, Lynn said.

Reid responded: “Absolutely. They showed up with the FBI and the public has no idea why to this day.”

Lynn asked Fredericks the same question as to whether a new attorney general could decide to release the redacted records.

“No, the right-to-know law controls this,” Fredericks said.

Lynn asked Fredericks if the Reams case had gone to trial, would the witnesses whose interviews are being protected have the right to tell the state they couldn’t be used at trial.

Fredericks responded: “I think that’s really outside of what’s happening here.”

Conboy asked Fredericks why he didn’t think Judge Smukler needed to do an in-camera review before determining whether documents were exempt from the right-to-know law.

Fredericks said the state offered Smukler two samples of the interviews so he could get a sense of what was being redacted that involved internal personnel matters. “I understand the concern. I think it’s within the trial court’s discretion whether to accept our characterization” of the documents, Fredericks said.

After the hearing, Reid said Foster has already released a selective version of that information in his removal complaint against Reams. “What they are really fighting for is to keep from having their actions and decisions scrutinized,” Reid said.

Fredericks also spoke with reporters after the oral arguments. Workplace victims won’t speak up if they are going to be embarrassed later, he said.

“It’s very private and if employees are going to be willing to participate in interviews regarding this conduct, they want to know that it is going to be kept confidential,” Fredericks said.

“It’s an area of concern,” Fredericks said. “There are real consequences.”