Page Jennings, right, is pictured with her brother Christopher Jennings.

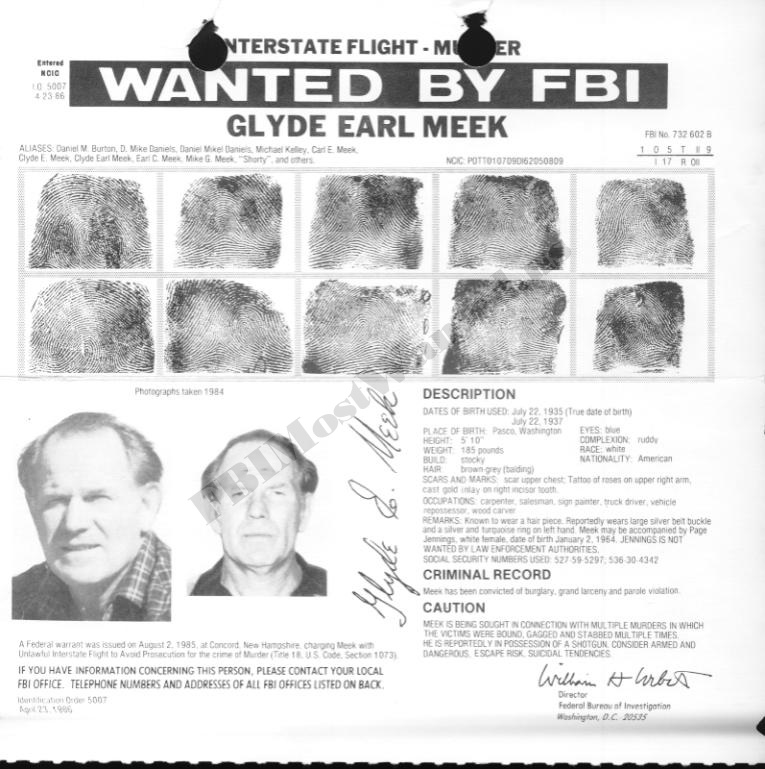

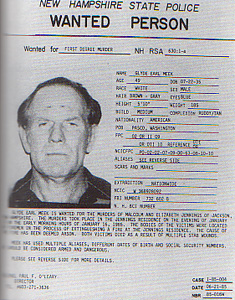

Glyde Earl Meek

Here Comes the Sun: InDepthNH.org founder Nancy West begins Sunshine Week Part 3 reminiscing about a simpler, kinder right-to-know era when a court hearing was held the same day the motion was filed in an infamous North Country murder case.

I filed my first right-to-know court motion one freezing cold morning in January of 1985 trying to get a photo police were circulating of an ex-con named Glyde Earl Meek.

Police wanted to talk to Meek, 49, in connection with the notorious murders Jan. 16, 1985, of Dana Place Innkeepers Malcolm and Elizabeth Jennings in Jackson. Meek had moved to Florida with their 21-year-old daughter Page and now they were found murdered in their home behind the inn, their bodies bound, repeatedly stabbed with their throats slashed.

It was a big deal. Then-Carroll County Superior Court Clerk John McLaughlin, an extremely kind and generous man to all, first coached me by phone in drafting my hasty motion, then scheduled a hearing for that afternoon in the beautiful old Carroll County Superior Courthouse in Ossipee.

“You can write a motion on the back of a brown paper bag,” McLaughlin said. It was my first lesson in how courts work – or at least worked in New Hampshire in 1985.

I have explained this at least three times over the years to different court clerks while scribbling out motions on my notepad. I could tell they didn’t always buy it, but persistence prevailed and the motions would be filed. Some day I plan to file a motion on an actual brown paper bag just to honor a really fine man.

“This is your court,” McLaughlin added. I often heard him say those same words to anyone who would listen when I was covering Carroll County for the New Hampshire Union Leader. It was their court, McLaughlin would say, and he believed it was his own, too.

The judge had to drive an hour and a half south that day from Berlin to Ossipee to preside over the hearing. Then-brand new Attorney General Stephen E. Merrill had to head north an hour from Concord with a car full of likewise suited up assistants ready to do battle with the state’s largest newspaper.

I was a correspondent in those days, a contract worker. There was no time to send the newspaper’s lawyer Gregory Sullivan to help. I was on my own.

The powers that be were more than a little annoyed to have come so far to face off against a lowly correspondent wearing jeans, mukluk boots and a baggy pink sweater my mother had knitted for me. (God knows why that detail sticks in my mind, although Monica was one hell of a knitter.)

My first court appearance was memorable, what I remember of it. I had a table to myself and had never even covered this kind of hearing before.

My oral argument consisted of one very, very, very long sentence. It began with an anecdote about an elderly woman who had started carrying a gun on her daily trips to the Jackson post office.

She was terrified, I told the judge, because there had been no arrest in the Jennings’ murders in the picturesque North Country town. I needed that photo to help relieve her fears. It had been such a horrific crime.

There was some legal garble, for sure – hastily taught by Clerk McLaughlin – about the six-pronged test to get records released during an ongoing police investigation.

And then it was over. My argument ended abruptly – to everyone’s relief – when I finally ran out of breath.

Merrill’s argument sounded to me like the Wah Wah language of adults in the Peanuts cartoons. The judge called a chambers conference with Merrill and wouldn’t let me in.

Attorney Sullivan, who is still fighting the good fight today, later obtained the notes from the chambers conference. The judge had asked Merrill who had the burden of proof in right-to-know cases. “Or are you just as much in the dark as I am,” he asked Merrill.

Bottom line: I didn’t get the Glyde Earl Meek photo. And just days later on Jan. 28, 1985, Meek and Page Jennings were found dead in Florida in a murder-suicide. Their bodies were burned beyond recognition in a shack. Found nearby was an eight-page suicide note.

The murder-suicide set off another mystery because it took so long to positively identify the couple, their bodes were so ravaged by the fire. Years later, Merrill said he should have given me Meek’s photo, although certainly not based on the strength of my legal reasoning.

I often wondered if police had found Meek during the 12-day window what might have been different, if publishing his photo could have helped save Page.

Here’s how the same photo request would play out today. I would first have to file a right-to-know request in writing with the Attorney General’s Office. A paralegal would send me a response within five days explaining why it would take at least 30 days or longer to respond to my request. (I’ve waited much longer than that on some requests.)

The last I heard there is only one very hard-working paralegal working on all right-to-know requests. Mine would be put in a queue.

If the attorney general ultimately declined to release the photo, most likely because it was part of an ongoing investigation, then I would have to file a motion in Superior Court. Sometimes the judge holds a hearing, sometimes not.

A handwritten Superior Court motion that I filed in 2014 with help from attorney Rick Gagliuso sought an unredacted copy of Attorney General Joseph Foster’s motion to remove Rockingham County Attorney Jim Reams from office.

The second amended complaint was released two months later as a result of the motion with the names of the women prosecutors who allegedly complained against Reams made public.

Glyde Earl Meek and Page Jennings would have been long dead in the time it takes today for the process to be completed, far beyond the 12-day window. And the law still protects ongoing police investigations from being made public.

I was lucky in many of the intervening years while working at the Union Leader that Attorney Sullivan filed the right-to-know cases, drastically increasing their chances for success. Today, I don’t see many newspapers filing right-to-know lawsuits. They are just too expensive.

What’s changed since 1985? It took much less time in 1985 than it would today for the state to refuse to release Meek’s photo, but I would have likely lost the case today as well. It would have just taken longer.

Here Comes the Sun Part 1 Secret Suspension: Right To Know Reams’ Suspension: Two Years and Counting

Here Comes the Sun Part 2: Is Your Government Keeping Secrets?