By TERRY FARISH, InDepthNH.org June 21, 2021

This is the story of how two people at a small group home turned to music in the pandemic. Catherine FitzPatrick and Michael Furlong have worked together since Michael left the Laconia State School, where he had lived for 10 years. In recent years, two things changed. First, Michael’s elderly adoptive mother died. Then life shut down with COVID-19. Grief and isolation were profound.

Catherine works for Psalm 33, Inc., a home care residential program in Greenfield directed by Catherine’s sister Mary FitzPatrick. Psalm 33, Inc. serves developmentally disabled people as one of Monadnock Developmental Services’ providers. Michael moved there a few days before his nineteenth birthday. Now he’s 56.

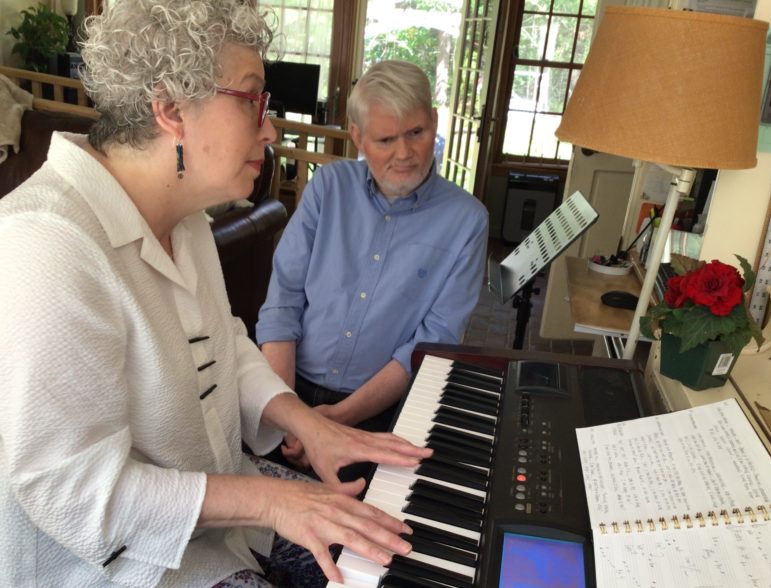

Catherine and Michael couldn’t talk through the losses of the pandemic. Michael has many disabilities with characteristics of severe autism. He experiences intense anxiety and seizures. He doesn’t have verbal language. He loves music. (His favorites include Chick Corea, Mozart, bird calls, and 99.5 on the radio.) Catherine is a composer who had studied composition at the New England Conservatory and the Berklee College of Music. So, in imagining what they could share to speak the words for grief and solace, it was natural for them both to turn to music.

Michael had always loved to listen to Catherine play the piano. During the pandemic, Catherine demonstrated how a composer makes choices in a chord progression. She invited him to make choices between two chords. Would he like a melody to go up or go down? Blinking meant yes. A blank face meant no.

They added “Creating Music” to Michael’s goals for his yearly plan with his care team that included his Service Coordinator, Ryann LaBombard, at Monadnock Developmental Services.

To explain their process, Catherine played a Ted Talk by jazz great Herbie Hancock. Hancock said he learned from his bandleader Miles Davis the idea of dropping the third and seventh notes of a chord. “It opened up the harmonies,” Hancock said in the Ted Talk. “It gives you more possibilities of things you can play.” Catherine hoped inviting Michael to write a song could help him make his feelings known in a new way.

A black music notebook became key to their work.

That’s where Catherine jotted their ideas, like character sketches. Michael had a planning board on which he selected the day’s activities. He often selected “Music, Breakfast, Write New Music” on his planning board. “Write new music” meant, get the black notebook.

If it was “Write New Music,” Michael chose between cards that said, “Play it” or “Work it.” If he chose “Work it,” he then would choose between “Timing” or “Feeling.”

Catherine played a chord, then wrote notations for the chords that Michael had chosen. They experimented. “What if we put the end of the song at the beginning? What if we repeat at the beginning? At the end? What Is the music trying to say? Where does the song end?”

They kept digging.

“Michael often chooses a sharp-11. A jazz thing,” Catherine said. “Sharp-11 expresses so much yearning. It leaves the song subtly unfinished.”

This was how, during the pandemic, they composed eight songs, including one inspired by the memory of Michael’s mother called “Mothers and Sons.”

It was then, a caregiver at the home, another resident, and Mary, the director, tested positive for COVID-19. Both Michael and Catherine tested positive. They had to quarantine separately. Michael got pneumonia. Catherine felt a fatigue that lingered.

While they were quarantined and they weren’t writing songs, Catherine talked about their journey with Michael. “We really feel he is brilliant,” she said. “We work on ways for him to learn how to ask for what he needs so that we can connect with his reality.”

At Laconia State School, Michael had been self-abusive. The staff had put Pringles cans on his arms like a sleeve so he couldn’t bend them and hit himself. Catherine said, “His language had been in his behavior. But those behaviors people couldn’t interpret as language.” Mary FitzPatrick added, “The staff at the state school had employed intrusive behavioral intervention in an effort to limit Michael’s extreme self-injurious behavior.”

In similar work to Catherine’s and Michael’s, music therapist Janet Graham wrote about her experience bringing music to non-verbal adults with communications disabilities. Her instrument was her singing voice; she and clients vocalized in response to each other’s vocalizations. In the British Journal of Learning Disabilities, she wrote that there was “a growth of understanding emotions beneath each other’s vocalizations. Clients could see themselves as communicating beings.”

Later, on Zoom, when Michael and Catherine were recovering from COVID, Michael wore a blue button-down shirt. His hair is white-blond, and so is his beard. His eyes shift from side to side. He lowers his chin and listens to Catherine play “Sunday Morning,” a song she and Michael had composed before they were sick.

There’s a driving wildness in the song that shifts to soft questioning and answering melodies. As Catherine plays, she describes how they worked the song. “If you start in the key of C, you could go down to a minor third or up a minor third. If we’d gone down, it would be so typical. We decided to go up to F, and that would open it up. What if we go down then?” she asked Michael.

“Then you thought of Dm7,” Catherine says to him of the Dm7 chord.

He blinks, yes.

“Then keep going down in thirds. Then back to the chord.” Catherine says, “Sorry, Michael.” She is playing so fast, she hit a wrong note.

He smiles.

About that sharp-11 that Michael loves, Catherine says, “I wanted to end the piece. But Michael kept wanting to bring out the sharp-11 relationship. He was very insistent about that. The song we wrote, “Mothers and Sons,” has so much hope. When I hear an element of yearning or joy in that song, I know Michael added that.”

They are working on their ninth song. Catherine says, “Right now it’s called, ‘That Song That Makes You Go and Get the Black Notebook.’” They have to decide where the song ends.

Sometimes with the sharp-11, Catherine says, “We just let the song linger.”

You can contact Terry Farish at tfarish@gmail.com

Terry Farish is a writer and novelist living on the Seacoast. She has written widely about contemporary immigration. Please contact her with ideas for immigrant and refugee stories, under-told stories, and stories that may not yet be part of the narrative of New Hampshire. She is especially interested in teen stories.