By NANCY WEST, InDepthNH.org

CONCORD – In two decisions Friday, the state Supreme Court overturned its own 1993 ruling known as the Fenniman case in what is widely seen as a victory for the public’s right to know about misconduct by public officials that has previously been deemed confidential.

The two cases were filed in the state Supreme Court by the New Hampshire Union Leader and Seacoast Newspapers after they were denied access to documents involving alleged police misconduct in separate public records cases under the internal personnel practices exemption of RSA 91a, the state’s right-to-know law.

In the first case, Seacoast Newspapers vs. the city of Portsmouth, a reporter was denied access to a union arbitrator’s decision after Portsmouth police officer Aaron Goodwin was fired because of a relationship with an elderly neighbor in which he inherited a $2.7 million estate, an inheritance that was later thrown out in court.

A Superior Court judge had ruled it was confidential under the internal personnel practices exemption. On Friday, the state Supreme Court overruled the decision and sent it back to Superior Court, while overturning its 1993 ruling in the case Union Leader vs. Fenniman.

“An overly broad construction of the ‘internal personnel practices’ exemption has proven to be an unwarranted constraint on a transparent government,” Justice Patrick Donovan wrote. “…(W)e overrule Fenniman to the extent that it broadly interpreted the ‘internal personnel practices’ exemption and its progeny to the extent that they relied on that broad interpretation.”

The 1993 Fenniman case involved an internal investigation of a Dover police lieutenant accused of making harassing calls. Then-Dover Police Chief William Fenniman had control of the internal records. The investigation found the lieutenant didn’t intend to harass but had lied during the investigation and was suspended for six pay periods.

The New Hampshire Union Leader sought memoranda and other records compiled during the investigation, but the state Supreme Court said at the time they were confidential citing the internal personnel practices exemption.

The Fenniman case has been cited numerous times over the years by government officials in keeping internal investigations confidential. It is also an issue in the case still pending before the state Supreme Court filed by the New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism and six news outlets against Attorney General Gordon MacDonald.

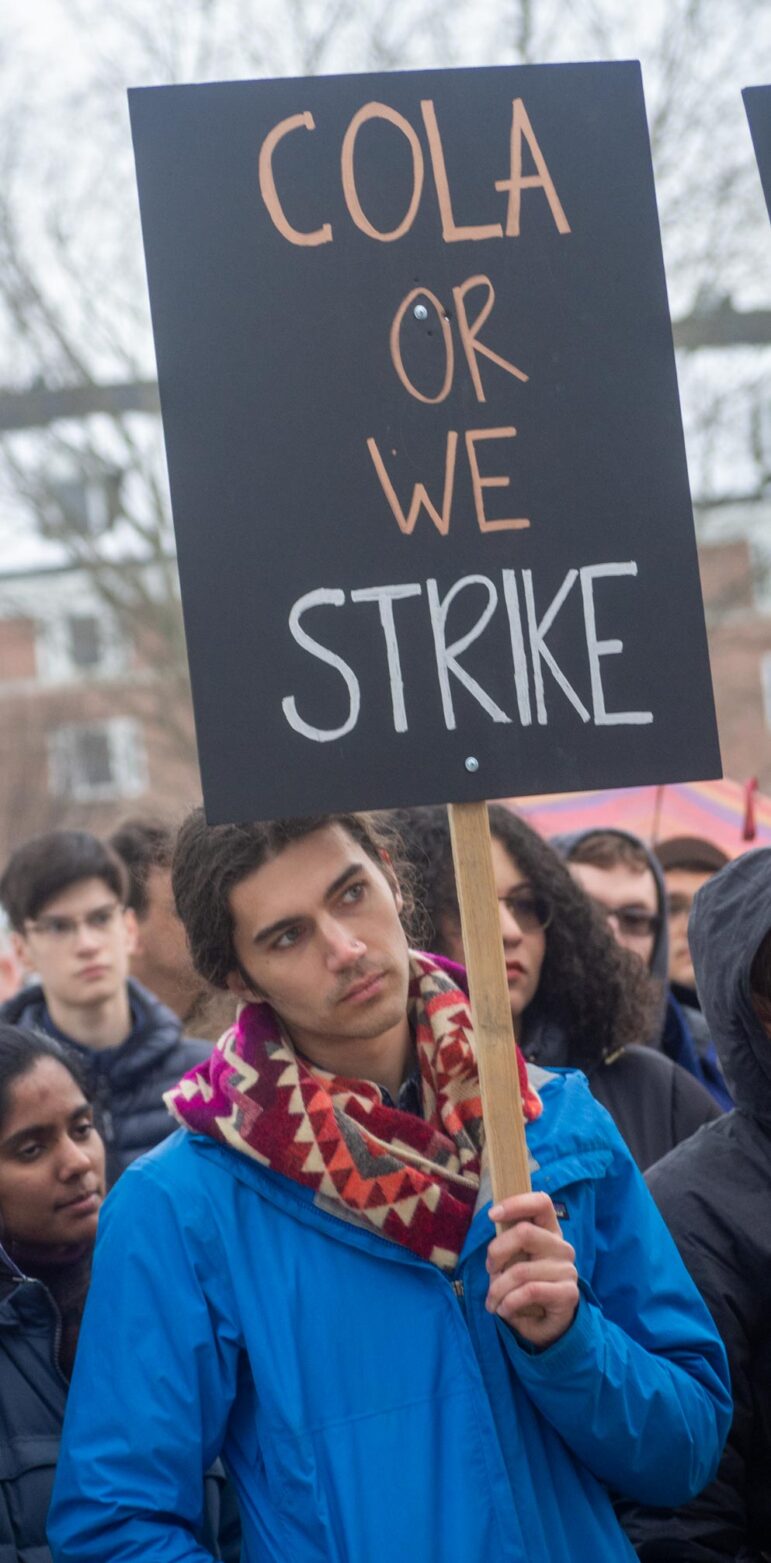

That case argues the Laurie List of police who have been disciplined for dishonesty should be made public. Another case pending before the court was filed by Keene State Professor Marianne Salcetti and her students.

The court said Friday: “The costs of overruling Fenniman’s interpretation are insubstantial and heavily outweighed by the rewards. As stated by the preamble of the Right-to-Know Law: ‘Openness in the conduct of public business is essential to a democratic society.’”

Gilles Bissonnette, ACLU-NH’s legal director, who has spearheaded several cases against the internal personnel practices exemption, said: “These historic New Hampshire Supreme Court decisions have restored the promises of transparency and accountability enshrined in our state’s Right-to-Know law and New Hampshire Constitution. In the two public records decisions, in which the ACLU of New Hampshire was co-counsel, the state Supreme Court overruled a case from 1993 that broadly allowed government agencies to withhold information under an ‘internal personnel practices’ exemption—even when there was a compelling public interest in disclosure.

“This exemption had been used by government agencies to prevent access to critical information, such as that concerning police officer misconduct or how a school district responded to allegations of sexual abuse by a former teacher. The New Hampshire Supreme Court’s decisions appropriately narrow this previously broad exemption, as well as require the examination of public interest to ensure government accountability in the Granite State,” Bissonnette said.

Manchester Attorney Rick Gagliuso, who was co-counsel on the Seacoast Newspapers case, said: “The public’s right to know about how its government operates is one of the bedrock principles of our state Constitution. The New Hampshire Supreme Court today took a bold step in favor of ensuring that essential right, overruling a line of cases that had stood for thirty years.”

Attorney Gregory Sullivan, who argued the 1993 Fenniman case, and numerous right-to-know cases over the years, is also co-counsel on Union Leader vs. Town of Salem, the second case the court overturned Friday. The Union Leader sought an unredacted copy of an audit focused on the Salem Police Department.

“The two decisions released today by the Supreme Court are victories for the public’s right to know what the government is up to. The New Hampshire Union Leader has been fighting for decades to shine the light of public scrutiny upon all public agencies, and nowhere is the public’s right to know more important than within the functioning of law enforcement agencies,” Sullivan said.

Sullivan credited ACLU-NH’s Bissonnette and Henry R. Klementowicz, “for their untiring efforts and advocacy. It was a collaborative effort.”

Supreme Court Justice Gary Hicks wrote in the Salem case: “In a separate opinion issued today, we overruled Fenniman to the extent that it broadly interpreted the ‘internal personnel practices’ exemption and overruled our prior decisions to the extent that they relied on that broad interpretation.

“We now overrule Fenniman to the extent that it decided that records related to ‘internal personnel practices’ are categorically exempt from disclosure under the Right-to-Know Law instead of being subject to a balancing test to determine whether such materials are exempt from disclosure. We overrule our prior decisions to the extent that they applied the per se rule established in Fenniman. We vacate the trial court’s order and remand for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.”

Justices James Bassett and Patrick Donovan concurred. Justice Anna Barbara Hantz Marconi wrote a dissent in both cases saying she disagreed with the need to overturn the Fenniman ruling.