Police-involved shootings in New Hampshire are almost always determined to be legally justified. In the Granite State, these investigations are conducted by New Hampshire State Police and the state Attorney General’s Office. But even in a generally pro-police state like New Hampshire, some say the shootings are justified far too often and suggest it’s time to empanel a civilian review board to examine them. This already happens in New York City and elsewhere. While race hasn’t been an issue in New Hampshire police-involved shootings as in some other states, the percentage of mentally ill people who are shot by police is far above the national average. And one former police officer who backs how investigations are conducted now, speaks out about killing a man on the job and living with the aftermath. This report was made possible by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

By NANCY WEST, InDepthNH.org

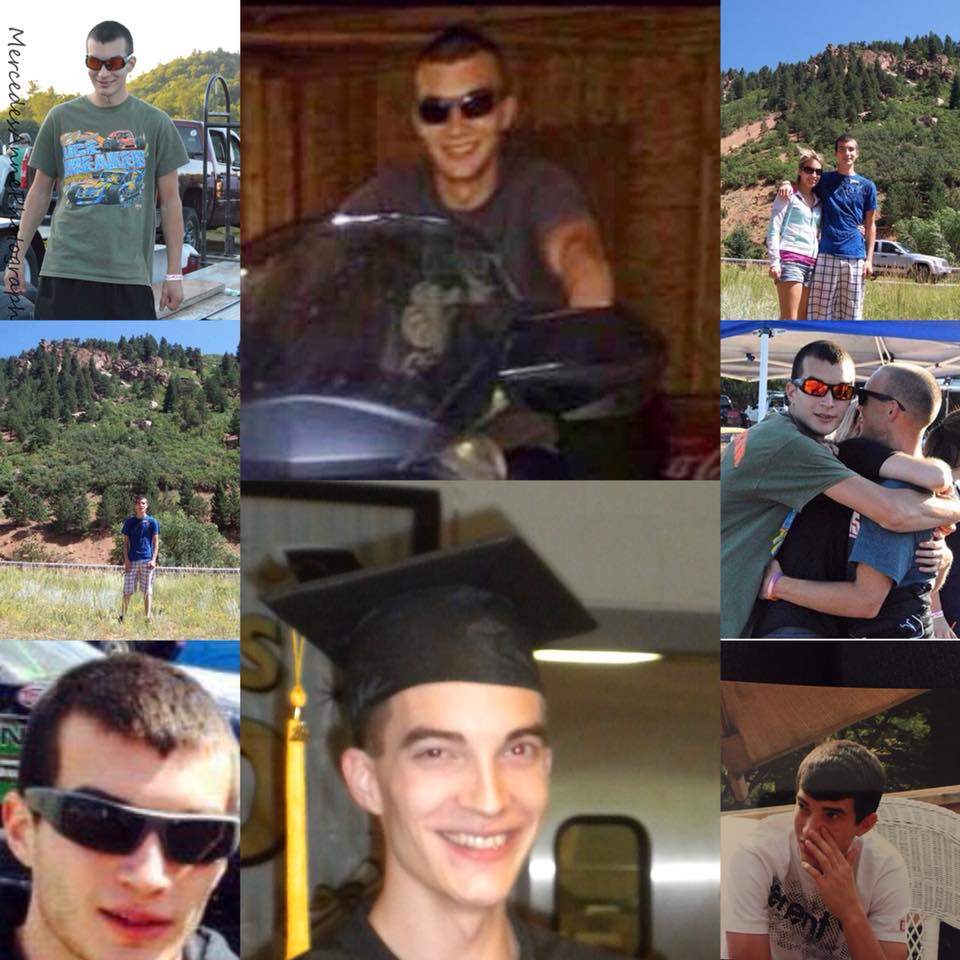

Cody Lafont was looking for help and a shoulder to cry on as he often did late at night when dialing 9-1-1 after drinking too much.

Claremont, N.H., police often obliged, stopping by the home that the lonely, depressed 25-year-old shared with his pitbull terrier. The officers sometimes engaged Cody in conversation long enough to convince him to sleep it off.

Other times, police took him into protective custody.

The last time Cody called 9-1-1 three years ago, he was due in court the following month to face charges of abusing the 9-1-1 emergency call system. He told friends he was worried about the possibility of going to jail as a result.

It was around 4 a.m. on Sept. 25, 2016, when Cody started calling police that day, becoming irked they didn’t show up right away. Friends had dropped him off at home after a night of drinking and attending the auto races.

Cody had texted his father earlier. He was worried, too, about missing counseling appointments his father was paying for to get him help for the major depression he experienced much of his life.

“Hey pops losing my mind agains [sic],” Cody texted.

And he kept calling 9-1-1. Finally, then-Claremont Police Cpl. Ian Kibbe was dispatched to Cody’s place to tell him to knock it off.

There was little conversation that early morning and no witnesses, no body or cruiser cameras, when Cpl. Kibbe knocked on Cody’s door with his flashlight just before 5 a.m.

Cody unlocked the screen door and was holding a bottle of vitamin water in his right hand and a black Colt revolver in his left hand, according to Kibbe’s account later to investigators.

The dog ran outside past Kibbe, who ordered Cody to drop the revolver. Cody had an odd smile on his face, Kibbe recounted, as he pointed the revolver at him.

Kibbe fired the three shots that killed Cody during the brief encounter. It had lasted less than one minute.

Like almost all civilian shootings by police, Cody’s death was investigated by State Police and the state Attorney General’s Office and deemed to be legally justified.

His family didn’t believe it from the start.

“It was senseless and we all just knew it,” said Tracy McEachern, Cody’s mother. “Cops investigating cops. I think they are all corrupt.”

After Cpl. Kibbe was convicted of crimes related to a search he conducted 18 months later in an unrelated case and was jailed for 90 days, Attorney General Gordon MacDonald reviewed the finding and recently changed the report so Lafont’s death is no longer deemed legally justified.

Kibbe pleaded guilty to obstruction of government administration and unsworn falsification in that case in which he and another officer conducted an illegal search, discovered weapons and lied about where they found them.

The amended conclusion now states: “Instead, the Office has concluded that it could not disprove Mr. Kibbe’s self-defense claim, beyond a reasonable doubt, and therefore no criminal charges will be filed against Mr. Kibbe as a result of Mr. Lafont’s death.”

56 Shootings

A review of the New Hampshire Attorney General’s reports of 56 police-involved shootings over 30 years, several lawsuits and documents, a State Police grant and interviews showed:

14 police-involved shootings were not fatal.

52 were determined to be legally justified.

4 were not deemed justified. No criminal charges were brought (including the Lafont case) even when the final report was critical of the police.

25 of 55, or about 45 percent of police-involved shootings in New Hampshire researched for a State Police grant, involved victims with a documented mental illness. Experts say the national average is 25 percent.

Time for change?

Mark Sisti, a well-known defense attorney who practices in Chichester and often represents high-profile clients, said it’s time for New Hampshire to involve civilians in determining whether police acted appropriately when using lethal force against citizens.

Sisti called Attorney General MacDonald’s reasoning in amending Ian Kibbe’s shooting of Cody Lafont “a goofy, illogical conclusion. I don’t understand it.”

Because so many of the police-involved shootings are swiftly deemed legally justified by the Attorney General’s Office, the rulings are not always viewed by the public as credible, Sisti said.

The law would have to be changed to create a civilian review board, which Sisti believes should include law enforcement, prosecutors, defense attorneys, forensic experts and lay people.

“This is still a police-driven legislature and the nature of the state instead of a citizen-driven state,” Sisti said. “My feeling always has been that there should be some neutral and detached review of police-involved shootings.”

People are skeptical of law enforcement doing their own investigations, he said.

“You can get rid of all that doubt by opening it to neutral people and it’s not hard to do,” Sisti said, pointing to citizen review boards in New York City and other cities around the country.

Police officers should be subject to the same scrutiny as anyone else, Sisti said.

“I think it’s an incredible coincidence that all the police officers are always cleared. That does create skepticism around the state when they read headline after headline that all the officers are cleared. If we had a neutral panel, there would be more credibility,” Sisti said.

State Rep. David Welch, R-Kingston, a member of the House Criminal Justice and Public Safety Committee, is an ardent supporter of police. He attends every graduation from the police academy.

Welch said it’s getting harder to recruit new police officers because society is changing and the job is considered too dangerous.

It’s also fraught with problems, including high divorce and suicide rates, Welch said.

Welch also believes there is a self-selection process in recruiting that sees more military veterans joining local police departments. If the veteran saw combat duty, he or she would have to be retrained for civilian police work, he said.

“Service in combat is a whole different thing than walking down Elm Street,” Welch said.

He would support a civilian review board to oversee police-involved shootings as long as it is balanced. It’s important that the public view the process as fair, he said.

The Attorney General’s Office comes down “a little too quick,” on determining the shootings are justified, he said.

“It doesn’t always allay the suspicions people have,” Welch said. While he supports police “almost 100 percent, they are human beings, too.”

Investigations

Associate Attorney General Jeff Strelzin said all police-involved shootings are scrupulously investigated and treated the same as any homicide probe.

The three other police-involved shootings that weren’t found to be justified besides the recent amending of the Ian Kibbe report included one in Nashua because the state didn’t have enough information to rule one way or the other, Strelzin said.

In the second case, the state could not disprove the officer’s self-defense claim beyond a reasonable doubt.

And the third involved an incident in Weare in which a suspected drug dealer was shot to death during a botched drug bust. The state didn’t have enough evidence to make a finding, Strelzin said.

As to Cody Lafont’s family believing a gun was planted at the scene, Strelzin said the ownership of the gun was tracked and Cody Lafont did in fact own it.

The difference between a justified shooting and one that isn’t is based on the certainty of the level of proof in the case, Strelzin said.

“When a private citizen or a police officer uses deadly force and claims they acted in self-defense, the state has the burden of proof to disprove self-defense beyond a reasonable doubt.

“So, there’s no burden of proof on the actor that he or she acted appropriately under the law. Once they raise the issue of self-defense, the burden of proof shifts to the prosecuting authority to disprove that claim beyond a reasonable doubt,” Strelzin said.

Although the Attorney General’s Office also represents State Police and other state agencies in its civil bureau, Strelzin said it is a totally separate unit and there is no communication between the two on such cases.

New York City review

The New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board, chaired by the Rev. Fred Davie, is credited with the recent resolution to fire Police Officer Daniel Pantaleo in the widely publicized death of Eric Garner five years ago.

Federal and state authorities had declined to indict Pantaleo. A video showing him using a chokehold while arresting Garner for selling loose cigarettes went viral. Garner kept saying, “I can’t breathe,” before he died. Outrage in that case and others showing lethal force against African Americans generated calls for reform.

In an opinion piece published in the Washington Post, Davie said the all-civilian review board received the complaint that led to Pantaleo’s firing.

“I hope that our experience on the board in the Garner case will prompt cities across the country to consider the value of civilian oversight of police.

“Holding law enforcement officers accountable and working toward better policing requires everyone to pay attention and speak up when appropriate,” Davie said.

The aftermath

Patrolman Tony Pivero was on patrol in Nashua, N.H., on a warm Labor Day evening in 2002 when his radio carried the excited description of a small pickup truck whose driver had just shot to death his ex-wife and a male friend. Her 9-year-old twin boys were home at the time.

The suspect, Joseph Collopy, 64, a former Massachusetts police officer, was seen fleeing his ex-wife’s apartment, according to police reports.

By the time Pivero’s cruiser pulled up beside Collopy’s truck at a red light just before 7:45 p.m., he had just crossed Veterans Bridge, near the Hudson, N.H., town square.

Collopy was intoxicated and obsessed with his ex-wife. Police believed he was on his way to settle another grudge by murder when Pivero stopped him.

Pivero said he pulled up beside Collopy’s truck.

“I looked to my right and we locked eyes,” Pivero said. He knew he had the right guy and quickly pulled in front of Collopy blocking him from leaving.

Sirens blaring, cruisers from Hudson and Nashua pulled up behind Collopy so he couldn’t leave.

Pivero’s adrenalin had already kicked in. Suddenly, it was on overdrive. Pivero exited his cruiser, positioning himself by the trunk. He was hyper-focused on the killer’s face – and staying alive.

Collopy put his gun, a .45-caliber, to his head at one point. Then he put it down in his lap.

“He lifted the gun again and started pointing it at me,” Pivero said. “I fired and all of sudden … chaos.”

Pivero thought 10 or 15 minutes passed, but likely it was just a minute or two.

Other officers started shooting as soon as he fired.

“It sounded like thunder. It was chaos,” Pivero said. “Then suddenly everything went eerily quiet.”

Pivero remembered walking up to the truck and saw a bullet hole in Collopy’s cheek.

“I went into police work to help people,” Pivero said. But he could no longer perform the duties he loved for 18 years and soon retired on disability.

At first, it was bizarre dreams, he remembered.

“In one, I was sleeping, and I felt someone rubbing my arm. And when I woke up the person over me who was rubbing my arm was Joseph Collopy…,” Pivero said.

“It was so lifelike that today I am convinced that it actually happened.”

Police officers often have a similar mindset, he said. They get into the business to help people, Pivero said.

“What turned him bad I don’t know,” Pivero said. The Collopy shooting was determined to be legally justified.

After retiring, Pivero went into construction work, but he can’t help wondering what life would be like had he never unholstered his gun that day.

He felt a kinship with Collopy after learning he had been a police officer in Massachusetts. In his dream, the face seemed real.

“It was the same face I saw that day – kind of an old man looking depressed. It was very scary because it was so lifelike,” Pivero said.

Pivero, who has been known to criticize the Attorney General’s Office in the past, believes the current system to investigate police-involved shootings works well under the direction of Associate Attorney General Strelzin.

View Part 2 and Part 3 of the interview by clicking on the links. Videos by EVAN LIPS.

Numbers game

Justin Nix, an assistant professor of criminology and criminal justice at University of Nebraska, said making sense of numbers when reviewing police-shooting deaths is difficult because there is no state or federal agency that keeps detailed records.

The Washington Post keeps fatal shooting data that remains steady at just under 1,000 fatal shootings a year nationally.

“We know that nationally, about 25 percent of those fatally shot showed signs of mental illness,” Nix said. “We also know that police frequently come into contact with people suffering from mental illness.”

On its face, more training, the use of crisis intervention teams, or pairing mental health workers with officers as they respond to calls involving people with known mental illnesses all seem like promising ideas, Nix said.

New Hampshire had 0.75 fatal officer-involved shootings per 1 million residents from 2015 to 2018. That ranks 42nd among all states and Washington, D.C.

There is no database that includes nonfatal officer-involved shootings.

The fact that most of the police-involved shootings in New Hampshire were ruled justified is not surprising, according to Nix.

Officers have the legal authority to use deadly force when faced with an imminent threat to their safety or the safety of others.

The available data consistently suggest that officer-involved shootings predominantly involve citizens who were armed with deadly weapons or were actively attacking the officers or other citizens – 82 percent had a deadly weapon, and 74 percent were either pointing/shooting a gun or attacking someone with a deadly weapon, Nix said.

“Given that such shootings are already a rare outcome of police-citizen interactions (a few thousand out of 52 million-plus in 2015), and most fall within their legal authority, I’m not sure what we should expect the number of officers charged to be, but I don’t think we should be surprised that it is small,” Nix said.

State Police grant

Retired State Police Maj. Russell Conte has three decades of experience in police work and more recently served as a board member for the National Alliance on Mental Illness-NH.

He helped write a $120,000 grant that will train 435 state troopers and fire/emergency personnel over the next three years in crisis intervention training to improve outcomes when dealing with mentally ill people.

“Between 1999 and 2017, there were 55 officer-involved shootings for all New Hampshire law enforcement agencies, of which 25 victims had documented mental health issues. In the same time period, the NH State Police were involved in 10 shootings, of which 5 victims had documented mental health issues,” according to the grant.

Conte expects the training will change the culture of state police and emergency first responders.

At a grant-funded training session earlier this year, Kim LaMontagne, a sales executive from Derry and a NAMI-NH volunteer, told about a dozen troopers how she suffered with mental illness in silence for many years.

She is now certified to train others in the “In Our Own Voice” NAMI-NH program. Using role play and personal anecdotes, LaMontagne explained how frightening it feels to have police show up at your door during a mental health crisis.

LaMontagne knows the feeling well as someone who suffers from major depression, anxiety disorder and who has been recovering from alcohol abuse for 10 years.

“I was that girl in the corner. I was that person who felt broken and empty,” LaMontagne told the group. “I had no hopes, no dreams…”

The troopers seemed unsure at first how to respond as she pretended to be a barricaded subject, but with LaMontagne’s encouragement, they began reaching out to her with growing confidence.

They asked calming questions about her children and family and eased her fears by telling her they didn’t park the cruiser in front of her home.

Cody Lafont’s mom

The sadness lingers for Lafont’s friends and family. His mother, Tracy McEachern, couldn’t find a lawyer as administrator of his estate to sue police until just before the statute of limitations would have run out in September.

Attorneys Charles G. Douglas III and Jared Bedrick filed the lawsuit Sept. 24 in federal court the day before the deadline. The Attorney General’s Office released its final report a week later, saying Kibbe’s shooting was no longer considered justified.

The lawsuit alleges that the city of Claremont, Brent Wilmot and Ian Kibbe knew or should have known that Cody Lafont suffered from a mental disability and was a “qualified individual with a disability” as defined by the Rehabilitation Act or the Americans With Disabilities Act.

“Instead of perceiving Lafont’s disruptive behavior as being the manifestation of mental illness, ignored obvious pleas for help, and instead instructed an officer to respond to the house to tell Lafont to stop calling for help,” the lawsuit alleges.

McEachern, who was a local businesswoman until she left Claremont last year, doesn’t believe Cody owned the revolver that police say was found on the ground near his body.

“I firmly believe it was a plant,” McEachern said.

She distrusts much of the investigation. “It still bothers me that State Police was not called for an hour and a half,” she said.

And she doesn’t believe Cody calmly opened the door for Kibbe with an odd smile on his face.

“When Cody was drunk, he was mouthy. I don’t buy that business of a smile for a minute,” she said.

Because of his drinking, the family had removed a safe from Cody’s house containing what they believed were all of his weapons. Before that, when he bought a gun, he bragged about it, McEachern said.

“He hunted. Whenever he got a new rifle, he’d bring it to my house or into the shop and say, ‘Hey mom look what I bought this weekend.’”

McEachern moved to Florida last year. “Being out of the area has made it easier in a lot of ways. I’m not always running into people in a small town,” she said.

The last time she saw her son was a week before his death. Sometimes the grief is hard to handle even three years later, McEachern said.

“You still have those days, you know,” she said.