Crime scene photo. Elizabeth Knapp, 6, was raped and murdered in her bed in a room she shared with her little sister in Hopkinton on July 3, 1997

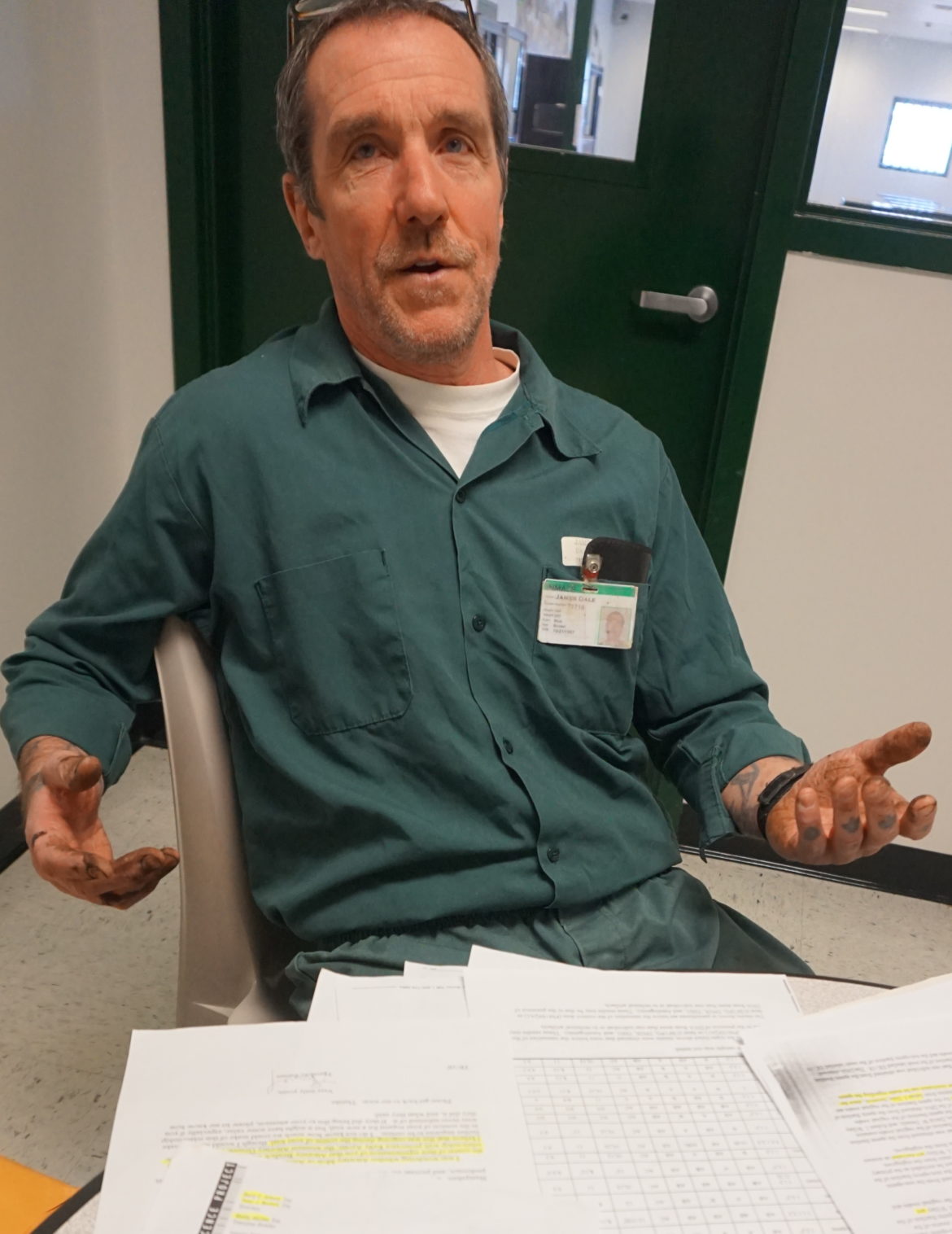

James Dale has filed a petition in federal court seeking again to receive a new trial in the rape and murder of six-year-old Elizabeth Knapp almost two decades ago in Hopkinton.

Click here for the petition.

For Dale, the reason he keeps fighting is simple, although it is unlikely he will ever be released from prison even if he were to be exonerated in Knapp’s murder.

Dale would still have to serve a 21 ½ – to 43-year sentence in Pennsylvania for trying to kill another inmate while he was incarcerated there. Having recently celebrated his 59th birthday at the Northern New Hampshire Correctional Facility in Berlin, he admits there is little hope of a future for him as a free man.

Still, he spends his days and nights on his latest appeal, a writ of habeas corpus filed in U.S. District Court in Concord in late June. Dale is waiting to hear if his case will be accepted.

“Because I didn’t do it,” Dale said.

He is adamant that he didn’t rape and smother Elizabeth Knapp on July 3, 1997, for which he was sentenced to serve 60 to 120 years in prison. The case was highly publicized at the time, and another man, Richard Buchanan, was arrested shortly after the murder then released five months later.

Dale insists he will prove his innocence some day — or die trying.

Dale readily admits to trying to kill the inmate in Pennsylvania. He concedes, too, that he has been violent and assaultive for most of his adult life, which has kept him in and out of prison during most of that time.

But when it comes to the rape and murder of a little girl, Elizabeth Knapp, who lived with her sister, Sara, mother, Ruth Knapp, and her mother’s boyfriend, Richard Buchanan, in an apartment downstairs from his at Perkins Manor, Dale is also adamant.

“I didn’t do it,” Dale said. “Yes, it’s the honest-to-God’s truth. I’ve done a lot of things. I should have been doing life years ago, but not for this.”

Nashua attorney Robin Melone, who represented Dale in his unsuccessful 2014 bid for a new trial in Merrimack County Superior Court, said although she no longer represents him, she hopes someone will listen to Dale this time.

New evidence she discovered while stringing together other serious concerns about his case for the appeal show Dale should have his day in court, Melone said.

“There are many aspects of the case that I find very unsettling,” Melone said on Wednesday.

In that appeal, new evidence revealed that one of Dale’s trial attorneys, Nicholas Brodich, and the prosecutor, Kelly Ayotte, who is now a U.S. Senator, admitted they were romantically involved within weeks of Dale’s sentencing. They were both single at the time and insisted nothing unethical happened.

Merrimack County Superior Court Judge Kathleen McGuire ruled that, “Even if an actual conflict still existed when Ayotte and Brodich were dating, (Dale) has not met his burden of proving” it would have impacted his case.

There were important problems with Dale’s 1999 criminal trial and a 2004 appeal that deserve a second look, Melone said.

While rummaging through moldy boxes of records that Dale’s mom kept for years in her basement, Melone found a letter that backed up her client’s statement. Dale had told Melone that his appeals lawyer in 2004, Brian McEvoy, told him he didn’t have to appear for the hearing.

Dale was incarcerated in Pennsylvania at the time and didn’t want to appear via video. McGuire dismissed the case without hearing the merits because Dale was a no-show.

“I remember the moment I found the letter from attorney McEvoy in which he told Jim he did not have to participate in the hearing,” Melone said. “I yelled to my co-counsel in the other room. It was validating.”

McGuire dismissed Dale’s 2014 petition and a motion to reconsider saying they were untimely and barred by laches, which means Dale delayed too long in seeking relief.

InDepthNH.org could not reach McEvoy at work or home and when contacted several years ago, he declined to comment.

“Even the best attorneys make mistakes,” Melone said Wednesday. “But the good ones own them and fix them.”

The court record is incomplete as to what McEvoy told McGuire, she said, and McEvoy declined to speak with her.

“But I can’t help but think that had attorney McEvoy told the judge that Jim declined to appear on advice of counsel that the judge would have ruled differently,” Melone said.

Melone initially challenged the effectiveness of Dale’s representation at trial by Brodich and Jim Moir. Dale, representing himself, has essentially used the same arguments in federal court that Melone used in Superior Court arguing that Dale’s trial attorneys failed to call Elizabeth Knapp’s mother, Ruth Knapp, as a witness.

Ruth Knapp had told police she saw her live-in boyfriend, Richard Buchanan, raping and killing her daughter, and that she tried to pull him off Elizabeth. Ruth Knapp threatened him with a steak knife before he dragged her back to bed, Ruth Knapp told police.

Buchanan was arrested and spent five months in jail awaiting trial before he was released after DNA samples failed to implicate him.

McGuire also found that the decision to not call Ruth Knapp to the witness stand “was reasonable and constituted sound trial strategy.”

McGuire quoted Brodich as saying that Ruth Knapp had given three or four different versions of the events and that she appeared hostile to the defense and had a “motive to try to help the attorneys general prosecuting the case.”

“Attorney Brodich indicated that these factors played a crucial role in trial counsel’s decision not to call her as a witness during the trial,” McGuire wrote.

Dale had moved to Arizona after Knapp’s murder, but state authorities brought him back to New Hampshire on a probation violation. Dale was later charged with and then convicted of second-degree murder and aggravated felonious sexual assault. A tiny amount of his DNA was found on Elizabeth Knapp, but that link is also problematic, according to Melone.

“Today, DNA is analyzed by machines. In Jim’s case, the DNA was analyzed by a person, making subjective comparative judgments about whether the DNA was a match,” Melone said. “There are just too many questions on that front.”

While interviewing Dale at the Berlin prison, he showed InDepthNH.org a letter from attorney Barry Scheck’s Innocence Project asking if Dale is still interested in their legal help.

Dale said he has provided the Innocence Project with the information they requested and is waiting to hear back from them as well. Scheck was co-founder of the Innocence Project, which is dedicated to using DNA evidence to exonerate people who have been wrongly convicted.

Attorney Brodich recently told InDepthNH.org that it was difficult to remember what happened so long ago. But he was certain that neither he nor Ayotte would have done anything unethical.

Ayotte didn’t respond to requests for comments, but two years ago, a spokesman provided the following statement to WMUR:

“James Dale is a despicable child murderer and rapist who Sen. Ayotte successfully prosecuted 14 years ago, and this is his latest desperate attempt to get out of jail. It’s indisputable that Sen. Ayotte, who was single at the time, did not interact socially at all with the defendant’s counsel during the trial.”

Melone said as an attorney, she understands there needs to be an end to the appellate process, a final judgment.

“But I am hopeful that someone will eventually look at the substance of what we drafted for Jim,” Melone said.

Dale said he is a different man today, but still doesn’t know why he was such a violent man who drank so much in his younger days.

Or like the man he was on Aug. 14, 2000, when he and his co-defendant Eric Thornton were serving New Hampshire sentences at the Correctional Institution at Graterford, Pa., pursuant to an interstate compact.

Dale was convicted of attempted murder and related offenses after an exercise yard incident in which he and Thornton attempted to murder fellow inmate Jason Selders by cutting his throat. They thought he was telling the other inmates they were snitches.

Today, Dale has a job at the prison and mentors younger inmates so they don’t follow in his footsteps.

For his birthday last week, some of the other inmates made him a special meal to celebrate.

“We do things for each other,” Dale said. “They cooked me a meal. It had chili and beef stew from the commissary and Raman noodles, seasoning, cheese, beef stick. We call it a batch.”

Dale restates his position, time and again.

“I will say on everything I love. I am not guilty. I will fight to the day I die.”