Residents Divided Over Sale Of Brown School in Berlin

By Thomas P. Caldwell, InDepthNH.org

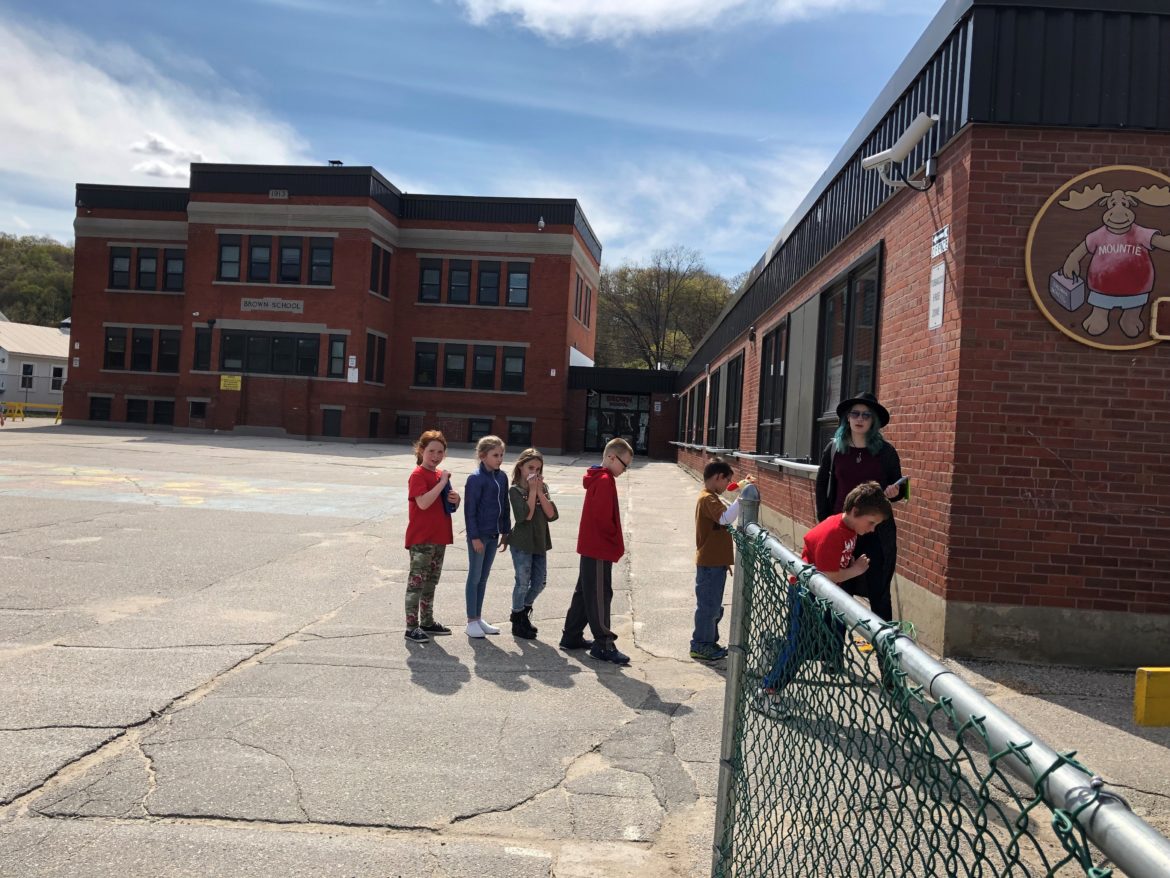

BERLIN — The future of the city’s Brown School appears settled, but residents remain divided about the outcome.

The Berlin City Council has approved New England Family Housing’s proposal to convert the school into affordable housing.

The plan calls for creating 20 to 22 residential apartments, 75 percent of them reserved for low- to moderate-income families.

Kevin Lacasse, the chief executive officer of New England Family Housing, noted that the income limits “are pretty substantial,” contrary to what many people think when they hear about low- to moderate-income housing.

“They’re higher than you would think,” Lacasse said. “In Coos County, the income limit for a single person would be $47,800; two people would be $54,600,” and the numbers go up to $90,100 for an eight-member household. Anyone at or below those income levels would be eligible for the apartments, and they would be able to remain in the apartment even if their incomes later increase above those limits.

The other 25 percent of housing units would be available at market rates and, after five years, all of the remaining units would be rented at market rates, Lacasse said.

What makes those units attractive is that Berlin’s median household income is $39,130, with rents costing an average of 35 percent of that income and rising.

City Councilor Mark Eastman said that what really got people upset was the city’s decision to sell the property for $1.

“The taxpayers are telling me that they’re flipping out over this,” Eastman said in telephone interview. “The main thing was when they said they’re going to sell Brown School for a buck; that’s what just flipped everybody. … And then the low-income part of it was secondary to that — the fact that not only are they just going to give it away, but they’re building more housing that we don’t need because there’s vacancies, and what we need is higher-end stuff.”

Eastman said he voted against the plan because he favored putting the building on the market, rather than issuing a request for proposals. “A bid and an RFP are two different things,” he said. “A bid implies you’re going to pay money for it. An RFP is just a proposal, what you want to do with it.”

He pointed out that the Brown School sits on Route 16 and is across from the city’s Riverfront Park project, potentially making it an attractive property for investors.

“There’s got to be commercial developers out there,” he said.

Lori Korzen is one of the citizens who planned to attend the city council meeting to oppose the affordable housing project until they saw an article in the Berlin Daily Sun announcing that the city was planning to go ahead with the project.

“We had about 25 confirmed residents willing to go last night and speak up,” she said in an email after the vote, “but after seeing this headline, 22 of them were convinced that there was no use going to the meeting.”

She continued, “We, the taxpayers, have put hundreds of thousands of dollars into that building and would love to see some return on the investment. For any deal to be made to sell that building for just $1 is a slap in the face to all Berlin taxpayers. The Brown School building is currently worth over $1,000,000 and is being sold for just $1.”

School Closure

The history of the Brown School dates back to 1853 when the Berlin Mills School District No. 4 was formed. After initially using a large room adjacent to the Berlin Mills Company Store, a new school was built in the 1870s, replaced by a brick building in 1913 that was named after the Brown family which had operated the city’s paper mills. A wing was added to the school in 1959.

By 2019, faced with declining school enrollment and increased costs, the school district decided to consolidate buildings and close the Brown School, which it turned over to the city.

Community Development Director Pam Laflamme, who is serving as acting city manager for Berlin, explained the closure decision this way during a telephone interview: “As the state continues to shift the cost for education, and we have to place all of that on the property tax … even though our housing prices have increased and our property values have increased in the last couple of years, we’re still amongst the lowest property values and the highest tax rates in the state, and so some very difficult decisions have to be made as we move along and try to provide services and education to our residents.”

With the school’s closure, the city became responsible for the maintenance of the building. The decision to sell the property for $1, Laflamme said, was about “getting the property back into a productive state in which we’re not carrying the costs of operating a vacant property.”

It was not the first time that Berlin has sold property for $1. The city previously sold the Bartlett School for the same price, and it sold the former Woolworth building for $1.

Eastman said the Woolworth deal made sense because the other option was for the city to spend $150,000 to tear it down, leaving “a big hole in the middle of Main Street.”

The Brown School, he said, is in “really good shape.”

“The asbestos has been abated. The lead’s been abated. It’s school kids in there, so you know it’s a decent-shape building,” he said.

Korzen said the Catholic Church was interested in purchasing the building for its private Catholic School, but the city turned the offer down.

Father Kyle Stanton said the church never made an offer for the building.

“We opened a small parish school in September 2019, and as part of our discernment process, our committee was looking for locations,” he said, “and during that time, I believe, the city announced that they would be closing the Brown School. We were looking into parish properties, non-parish properties … and at the time they had not formally put the building on the market, or the city had not expressed what was going to happen next. So we never made a formal offer on the building or even a formal request for the building because it was never posted for sale at that time.”

When the city made it clear that officials were looking for taxable income from the property, the church, as a nonprofit entity, did not pursue the Brown School and ultimately settled on property it owned in Gorham. “We had to keep moving forward,” Father Kyle said.

Renovations to the building in Gorham have served the parish well, he said, but now the church is considering adding high school classes, which the Gorham campus, serving pre-kindergarten through Grade 8, would not support.

“The truth is, we’re outgrowing that building,” he said, “so now we have to look for a location to expand into high school.”

Twin Proposals

When the city of Berlin issued a request for proposals in 2019, only two companies came forward with plans for the Brown School: New England Family Housing and Wildcat LLC. At that time, the city council awarded the bid to Wildcat LLC, which planned to build 17 housing units while maintaining the school’s gymnasium for community use.

Wildcat ultimately was unable to gain the financing for its original project, and the city issued a second RFP in 2021, with the same two companies responding. This time, the proposals were similar, with Wildcat also proposing 20 living units, but offering to reserve some of them as short-term rentals for traveling doctors and nurses from Androscoggin Valley Hospital. It maintained the offer to keep the gymnasium available for community use.

A committee that had been formed to vet the proposals chose New England Family Housing. Laflamme said that, although the second round of proposals had nearly identical plans that relied on government grants, “I think maybe the edge was given to New England Family Housing because they had experience with what they were proposing using different federal funds.”

New England Family Housing has built and rehabilitated several buildings around the state to create affordable housing, including Bristol, Claremont, Franklin, Laconia, Rochester, Rumney, and Tilton, and has 80 housing units in Berlin, including some in the former Bartlett School.

Kevin Lacasse said in a telephone interview that not all of their projects have used the same funding mechanisms, but this one requires a combination of bank financing and government financing to make the project viable.

“The problem is, the cost of construction is so high, and the rents, especially up in Berlin, are very low — the lowest in the state. So to construct a project like that, if we just used our own cash sources or bank financing, the rents that would be produced … wouldn’t even support the cost of construction, even with getting the building for free,” he said. “So, in order to get the project to work, we need to apply for other types of funding sources.”

The main funding source for the project is a community development block grant, obtained through the city, which carries with it the requirement that the money will support low- to moderate-income residents. Laflamme said that Berlin has a good track record of obtaining CDBG grants for projects like that, so she expects the funding to come through.

Lacasse said a lot of people think the project is based on a voucher system where people move in and the government pays their rent.

“It’s not like it’s a tax credit deal,” Lacasse said. “A [Section 8] Low Income Housing Tax Credit project is completely different, and that’s not what this is. Everybody has to apply on their own merit.”

That said, “if somebody has a tenant-based Section 8 voucher and they meet all the qualifications, then, sure, they could be living there. But that same holds true for every apartment anywhere.”

Eastman believes the city’s 406 low- to moderate-income rental units already in existence will meet the need, although on the higher end, he acknowledged that there is room for apartments to accommodate police officers and construction workers involved in redevelopment efforts in the city.

Lacasse addressed another of Korzen’s complaints: that his aunt, City Councilor Lucie Remillard, had advocated for his company rather than abstaining or even acknowledging a potential conflict of interest in the matter.

“I grew up in Berlin and Berlin is a small town, as you know,” Lacasse said. “Everybody’s related to everybody.”

Lacasse said his mother’s sister is married to Remillard’s brother, “so we’re related through marriage, but not through blood. And to be honest with you, at a family function, I haven’t seen Lucie since I was probably about six years old. Our paths have crossed, obviously, because of her place on the city council and so forth, but there’s certainly no favoritism because of that family relationship.”

He concluded, “I take a lot of pride in that [project] because I grew up in Berlin, and that’s where I went to elementary school. … We do projects throughout the state — we own and manage over 600 units — but I’ve always had kind of a soft spot for Berlin just being from that area. So, you know, our intention is to make this the best project that we can.”

T.P. Caldwell is a writer, editor, photographer, and videographer who formed and serves as project manager of the Liberty Independent Media Project. Contact him at liberty18@me.com.