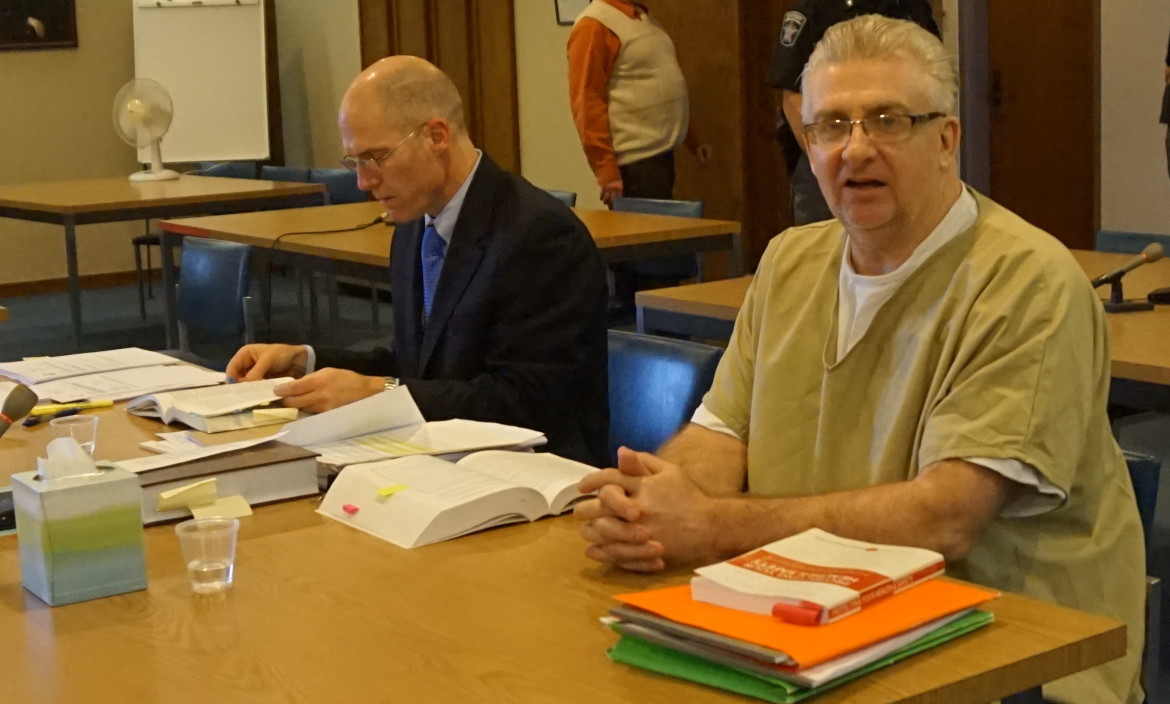

Eric Largy is pictured after his arrest seven years ago.

Eric Largy’s arrest seven years ago for allegedly “torturing” his father, retired Nashua Police Chief Clifton Largy, and handcuffing him to an antique barber chair for 12 hours shocked Nashua and the rest of New Hampshire.

The mug shot of him sporting a mohawk hairstyle and looking anything but competent to stand trial were all over the news.

Early on, Largy, who is now 49, complained to police that he was defending himself that day from his abusive father, insisting his father was interfering in his criminal case to protect the image of law enforcement from being tarnished by domestic violence.

“I’m not being paranoid,” said Largy during a recent interview in a small room at the Secure Psychiatric Unit at the State Prison for Men in Concord where he was civilly committed five years ago. “This is a pattern of behavior that I have seen going on in law enforcement in my case.”

Police, prosecutors and judges in the Nashua area all knew his powerful father, Largy has maintained since the incident.

Largy is a tall, imposing man. He appeared for an interview with InDepthNH.org to be calm, cordial, kind, well-groomed and articulate – just as he is described in treatment notes and by psychiatrists who testified last month at his recommittal hearing in Merrimack County Probate Court. The mohawk is gone.

Dr. Daniel Potenza, a psychiatrist and medical director of forensic services at the Department of Corrections, described Largy as a “complete gentleman,” during the hearing. Potenza also said Largy is diagnosed with a delusional disorder, and in his opinion, should be recommitted for six months.

Charges against Largy in connection with the incident – kidnapping and first-degree assault – were dismissed after he was involuntarily committed to the Secure Psychiatric Unit for five years after awaiting trial for two years at the Valley Street Jail. But the state can refile the criminal charges any time until April 2, 2018, when the statute of limitations runs out.

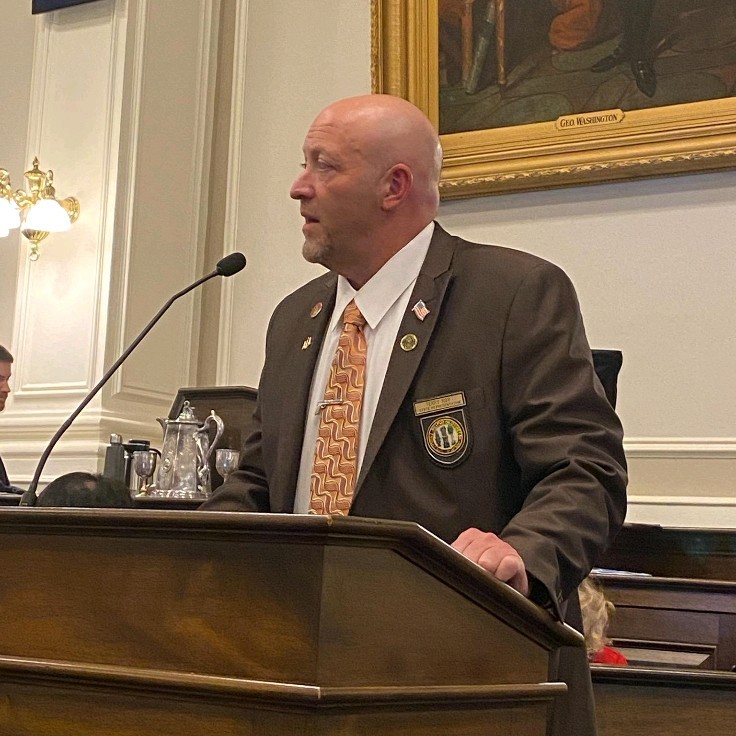

Father’s view

The senior Largy adamantly denies being abusive or influencing his son’s case. He suffered broken eye sockets and a broken jaw that day on April 22, 2009, and insists it was a premeditated attack.

“Of course it’s not true,” Mr. Largy said of his son’s allegations. “You can talk to anybody. Ask anybody.”

Largy was well-known when he served as the chief of police in Nashua, the state’s second largest city, before he retired. Talking about the incident during a phone interview dredged up ugly memories for him. No one from his family has had any contact with his son since that day.

“I don’t want to go through this mess again. What it does to me and my family, we’re broken up enough over what happened,” Mr. Largy said.

As to his son’s allegations: “If that’s what he thinks, I can’t help him. As far as I’m concerned, I did everything I could for both my sons.” Mr. Largy said he hopes the state will do whatever is in the best interest of his son and the public. His version of the violent incident is much different from his son’s.

“There was no self-defense. None. It was a plot and he hit me from behind,” Mr. Largy said. “I guess he should be ready to go to court and go to trial.”

There was no child abuse or domestic violence in his home, Mr. Largy said. “All I ask is that he gets the help he needs. If he is able to go and function outside, if it’s a safety issue, let them bear the responsibility.”

“Maybe he should ask the attorney general or somebody if they think he’s ready to go to trial. He should go to trial if he is competent to be on the street,” Mr. Largy said.

Instead of taking responsibility, his son chose to claim it was a plot against him, he said. “It’s the same old thing, blame everybody else.

“The doctors know the condition of that young man. They know his condition if they think he’s OK to go to court or OK to do whatever,” he said.

He remembers the day clearly. “If they say he’s OK and safe to be out there, that’s their choice, not mine. I saw that event, the plotting. That’s it. Something snapped. Whatever happened wasn’t nice,” Mr. Largy said.

Eric Largy has insisted at every turn that he has been unfairly treated because of his father’s political, court and law enforcement connections. That includes being effectively silenced when Largy was found incompetent to stand trial and civilly committed to the Secure Psychiatric Unit, he said.

Those housed in the unit are considered patients. The Department of Corrections is in charge of their psychiatric treatment and doesn’t release any information about who is housed there, not even their names.

The committal hearings and treatment notes are all confidential. Largy chose to open his March recommittal hearing and provide documents to InDepthNH.org to shine light on what he views as a miscarriage of justice that has robbed him of seven years of his life.

Reality or delusion

Largy’s insistence that his father abused him and pulled strings in his case provided fuel for psychiatrists to diagnose Largy with a delusional disorder.

They also served as the basis for him to be found incompetent to stand trial and to be involuntarily committed to the Secure Psychiatric Unit. The state, in fact, still points to Largy’s “conspiracy” as reasons why his commitment should be extended.

Assistant Attorney General Megan Yaple also wrote in her motion to recommit Largy for six months that he is “in such a mental condition as a result of his mental illness as to create a potentially serious likelihood of danger to himself or to others.”

Yaple also noted that he had not had any behavioral problems and was able to follow the rules.

Domestic violence

Largy often mentions statistics involving domestic violence in law enforcement families and insists the authorities want to sweep the problem under the rug.

“There were encounters within my relationship with my father that were aggressive and of a violent nature,” Eric Largy said. “That’s not to say that he’s a bad person or anything like that. It’s very hard. You’d have to have a domestic violence person to understand these things.”

By all accounts, Largy was not involved in any violence before that day – and has not been involved in any since.

Had he had the opportunity at trial, Largy wanted to prove that he was defending himself and even restrained his father because he was afraid of how he would retaliate against him.

Progress notes

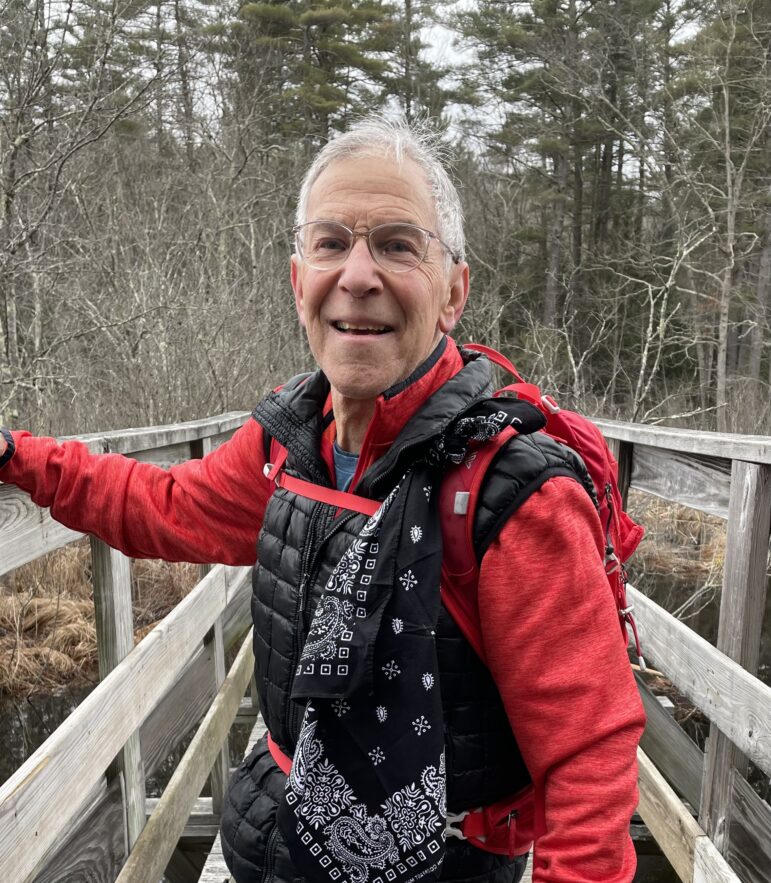

Although testimony at the hearing indicated Largy has refused to speak with treatment providers during his entire stay at the prison psychiatric unit, his lawyer Shane Stewart reminded those who treat Largy today about progress notes in Largy’s file that showed he was very forthcoming when he first arrived.

“The patient claims that his father started poking him in the chest and raised his hand to strike the patient. The patient claimed he feared for his life and a fight ensued,” wrote Jack Gavin, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, in a progress note dated April 15, 2011.

Largy told Gavin that there was no premeditation, that he never hit his father after he tied him to a chair then offered to take him to the hospital and allowed him to use a cell phone to call for help.

Largy told Gavin that his father abused him from childhood until age 42. “The patient claimed he loved his father very much and emulated him,” Gavin wrote. “He felt remorseful about the situation and felt it would not be possible for them to ever have a relationship again.”

At the time, father and son were involved in business together. “He claims he feels ‘sad’ for his father,” Gavin wrote.

Another progress note by senior psychiatric social worker Nora Bowen on Jan. 11, 2011, said: “Cont’s to state he is here due to a conspiracy that his father and the Nashua police have engineered. Does make some very good points. His behavior continues to be in good control.”

On Feb. 8, 2011, Bowen wrote: “Cont’s to talk about how his father has conspired to keep him here with all his legal/police connections. Story does sound plausible.”

In the state’s motion to recommit Largy for another six months, which has almost run out because of delays, it restated Dr. Nicholas Petrou’s original reasons why Largy should be found incompetent to stand trial.

“Dr. (Nicholas) Petrou stated that Mr. Largy’s delusional and paranoid beliefs and preoccupations about his father and the legal system were so pervasive that they would likely cause Mr. Largy to make decisions based upon a paranoid and distorted understanding. This would then affect Mr. Largy’s ability to rationally understand his legal situation and would interfere with Mr. Largy’s ability to collaborate with his attorney,” according to a motion filed by Assistant Attorney General Megan Yaple.

Largy could be released in as soon as four weeks, depending on how a judge has ruled since the hearing. It was filed as a confidential order, but Largy said he will ask the court to make it public.

The state could keep seeking further extensions, Stewart said. “He could be there for the rest of life,” Stewart said. “And he shouldn’t be there now.”

Stewart said no one except the father and son know what happened that day, but he tends to believe Eric just as some of his early treatment providers appeared to.

Hearing testimony

Recommittal hearings are usually closed to the public and press, but Largy asked that it be open. Largy said he is speaking out now in hopes of bringing some attention to his case.

Dr. Potenza was asked at the hearing if he would have any concerns about Largy being released into the community. “I would,” Potenza said.

He went on to say that his belief stems from the fact that Largy still possesses “a lot of the beliefs that led under stress to the violent event that occurred with his father.”

He conceded that Largy has exhibited no violent behavior at the Secure Psychiatric Unit.

“Since Mr. Largy has been at SPU, he has been a complete gentleman,” Potenza said.

But that is a very structured environment, he added. “This is not about Mr. Largy’s character. This is about his delusional belief and that stress can cause Mr. Largy to act out of character,” Potenza said.

Asked if he believes Largy is an appropriate candidate for recommitment, he responded: “I do.”

The future

Probate Judge David King has issued a confidential order. Largy read some of it to InDepthNH.org during the interview.

It said another petition for more time may be forthcoming. Largy has been ordered to the much less restrictive New Hampshire Hospital, but there have been some roadblocks to moving him there.

King’s order also said he hoped Largy would understand the state is not interested in trying to keep him locked up for the rest of his life, according to Largy.

Still, Largy doesn’t understand why he hasn’t been stepped down to the New Hampshire Hospital much sooner where the treatment is provided under the direction of the Department of Health and Human Services.

At the New Hampshire Hospital, Largy will be able to earn privileges such as walking outside on campus and could potentially leave the Concord campus with permission.

“I have been here for five years and have absolutely done no bad behaviors. I’ve done nothing wrong. I got a little job up here.

“I’ve seen guys come and go from here that have assaulted officers, that have planned criminal thinking and they’ve moved forward,” Largy said. “What is it about my case? What does my case represent that is keeping me here.”

If transferred to New Hampshire Hospital, Largy said he would consider undergoing treatment.

“I would probably be treated bodily and mentally and emotionally better… The treatment here is horrible and so are the living conditions.”

Largy has complained since he arrived about the processed food and lack of appropriate exercise, which he believes caused him to undergo major heart surgery last November.

Stewart said the state has to prove that as a result of mental illness, Largy is still a danger to himself self or others. Stewart said it is possible that Largy and his father got into a fight, that the son overcame his father, then restrained him out of fear of how he would retaliate.

“We’ve never had that conversation,” Stewart said, but that’s what he has surmised from the record and treatment notes.

Stewart said had Largy gone to trial and been convicted, he would have likely finished serving his time by now. Stewart said either Largy’s right or he is wrong and his father didn’t influence anything.

“But if Eric’s right and he did, is he delusional? No. If Eric’s right, then we have a problem,” Stewart said. “He’s not delusional if what he’s telling is the truth.”

Whichever is the case, Largy has been locked up for seven years, including two years at Valley Street Jail awaiting trial, and if he is released soon will have to learn how to live on his own.

“He doesn’t know how to go to the grocery story any more. He’s become institutionalized. Eric’s a bright guy, but he’s told what to do every day,” Stewart said.

The Secure Psychiatric Unit has become the focus of controversy for housing people like Largy who haven’t been convicted of a crime with men and women who are mentally ill and have been convicted of serious crimes, including murder and rape.

Largy still complains about the same issues regarding abuse and political interference by law enforcement, but uses general terms.

“I can’t discuss my case. I can’t trust law enforcement to do the right thing in situations like mine so therefore I cannot discuss it with the statute of limitations hanging over my head.

“I believe there’s a problem within the law enforcement culture with violence,” he said. “I am suggesting that law enforcement violence is a dirty little secret and they do not want their image tarnished or tainted in any way.”

Asked if his father and the rest of his family would be safe if he is released, Eric Largy answered, “Absolutely.”

In fact, he would like to rekindle a relationship with them.

“It would have to be done in the right way with a lot of thought,” Largy said. “I have obviously thought of that for seven years — how we would go about doing that.”