Some commission members studying how to provide due process for law enforcement while protecting a defendant’s right to know about a testifying officer’s potential dishonesty share opinions as they prepare to report on Nov. 1

Members of the Commission on the Use of Police Personnel Files and two people who testified before it have differing views about how to be fair to police and to defendants.

A key issue continues to be confidential Laurie lists of potentially dishonest police officers kept by prosecutors for possible disclosure as constitutionally required. Click on headline for the opinions of several commission members and interested parties in their own words.

The commission will meet for the last time before reporting on Wednesday at 2 p.m. in the Legislative Office Building in Concord. The public is welcome to attend.

Included below are complete statements from commission members Rep. Claire Rouillard, deputy majority whip who serves on the judiciary committee; State Police Sgt. Marc Beaudoin, representing the New Hampshire Troopers’ Association and the New Hampshire Police Association; Nashua Attorney Robin Melone, representing the New Hampshire Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, and Londonderry Police Chief Bill Hart representing the New Hampshire Association of Chiefs of Police.

Non-members who testified at the commission meetings Steve Arnold, representing the New England Police Benevolent Association, and Concord Attorney Jim Moir, an expert in Laurie issues, also responded to requests for opinions.

InDepthNH.org, a nonprofit investigative news website, seeks to shine a light on this controversial issue by presenting as many points of view as possible. We appreciate the willingness of those who shared their opinions in their own words.

Rep. Claire Rouillard, Assistant Majority Whip who serves on the Judiciary Committee

There are two objectives, as I see it with SB72. One is to make certain the accused defendant is provided with due process under the law, which requires that any exculpatory evidence be provided to the defendant. The other objective is to make certain that police are provided due process before they are put on the Laurie list, and a mechanism to be removed from that list.

The U.S. Supreme Court and N.H. Supreme Court have placed the burden to provide all exculpatory evidence on the prosecutor. The Courts have not required that a Laurie list be created. Rather, the Courts have held that there must be a “process” in place to provide exculpatory evidence to the accused.

That process could be the prosecutor should review the personnel file (or a portion thereof) of each police officer who was involved in the arrest and/or who will testify in the case, and provide that exculpatory evidence to the accused.

If the prosecutor has a question on whether information contained in the police file should be disclosed, a review by a judge should be obtained. If this process is followed, there would be no need for the Laurie list. I would recommend that New Hampshire, like other states, operate without a Laurie list.

If there is no Laurie list, the second objective to make certain that police are provided due process regarding placement on or removal from the Laurie list is met.

Lastly, because there is a difference of opinion as to whether prosecutors have the right to review police personnel files under New Hampshire Statute RSA 105:13-b, we need to make certain the language is clear and amend that statute to reflect that right of every prosecutor.

This change will also provide a mechanism for the attorney prosecutors to comply with their ethical obligations under New Hampshire law.

This is a difficult issue. Defendants, police and prosecutors would like to see changes to protect the rights and obligations of all involved.

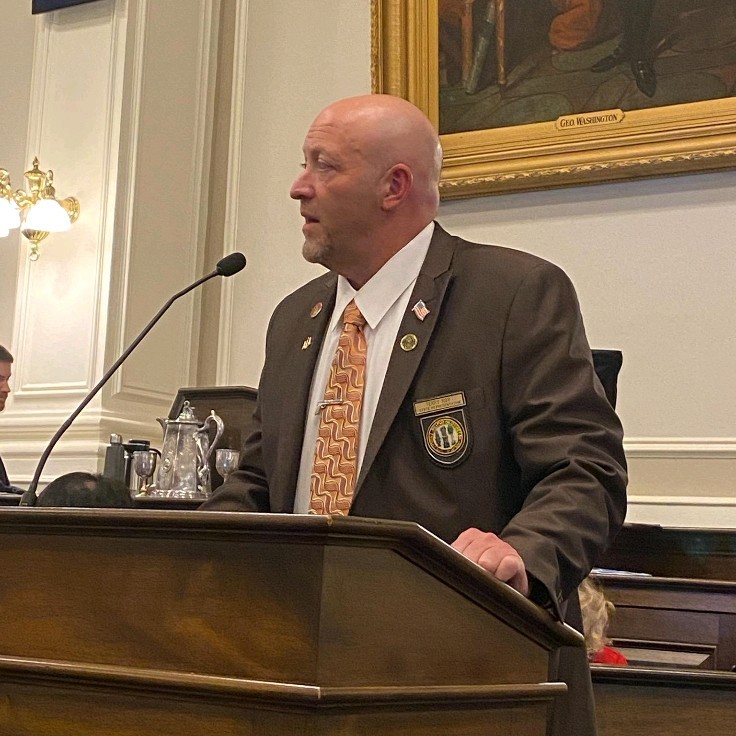

State Police Sgt. Marc Beaudoin, represents state troopers as president of the New Hampshire Troopers’ Association and also represents the New Hampshire Police Association

What we’re looking for is notice and a chance to be heard – basically due process rights. What we have found is some officers weren’t even notified that they were on the Laurie list. Other times, the person is deemed to have Laurie issues and is suddenly terminated, not for the underlying discipline, but more because of the stigma for being on the Laurie list.

If you are in a union, you have some post-deprivation rights. There are some remedies that the members may have after they have been disciplined or terminated. What we’re looking for is some kind of quick hearing (Pre-Deprivation Rights) prior to any officer being placed on the Laurie list.

Who would be doing the hearing? We would be comfortable with the court because they are truly neutral and detached. In the Duchesne case, the court said that the courts are the only one that can make that determination of whether an officer has a Laurie issue or not.

That takes it away from the chief of police, the prosecutor, and/or the county attorney. A lot of times, they will err on the side of caution and put someone on the Laurie list.

This also occurs a lot where some departments say that they do not want to employ officers with a potential Laurie issue, and as a result terminate them.

We are looking for some type of mechanism where the chief of police/prosecutor can submit their internal affairs finding to a court and the officer can also submit an argument to the court in his/her own defense. The court can review the incident and decide whether or not the officer should be placed on the Laurie list.

If the officer is placed on the list, at least he/she had some type of pre-deprivation rights (notice and hearing), and he/she will still have his/her post-deprivation rights, especially if they are in a union. If the officer is deemed not to have a Laurie issue and is not placed on the list, then the officer can be disciplined for the underlying issue and it’s been resolved without upending a person’s whole life.

One officer was on a department for 16 years. He violated a department policy, it was investigated, and he was deemed to have a potential Laurie issue by the chief of police. This department did not wish to have an officer working within its ranks that had a Laurie issue, so it terminated the officer’s employment. The policy violation would most likely not have been a terminable offense in and of itself. This officer was the sole bread winner; his wife doesn’t work, and he has two children. There is no pre-deprivation hearing right now (this is what we are lobbying for), but he does have his post-deprivation rights through his union. However, that may take several years to exhaust, and in the meantime his whole family life has been turned upside down.

A simple hearing could have been held before-hand. A judge could have examined the department’s internal affairs investigation along with any argument submitted by legal counsel, as well as an argument submitted by the officer through his/her attorney. The judge could make the determination after reviewing everything. If the officer is deemed not to have a Laurie issue, then he/she could just be disciplined for a minor policy violation and move on. If he/she is put on the Laurie list, then he/she still has his/her post-deprivation rights to exhaust.

The vast majority of police officers in this state are professional, and we have no patience for “bad” officers. That is the last thing we want, because it makes us all look bad. However, we do believe that officers should have the basic due process rights of being notified and a chance to be heard.

Nashua Attorney Robin Melone, representing New Hampshire Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

My hope is that the legislation that results from our work on the commission will be responsive and not reactive. Both the U.S. and N.H. constitutions are clear that criminal defendants have a right to be provided with potentially exculpatory evidence in police personnel files. That cannot be legislated away. The real issue here is how and by whom that information will be gathered, maintained, and dispensed. The prosecutors have an affirmative duty to disclose information about an officer they believe is potentially exculpatory. The prosecutors, not the police officers, should be the ones deciding what is potentially exculpatory.

I respectfully disagree with those arguing this is a personnel issue being shoehorned into a criminal due process issue. I understand and respect the desire of law enforcement officers to have due process in personnel matters.

And I don’t disagree that there should be a process in place whereby officers are notified of the conduct believed to be potentially disclosable under Laurie and Brady and have an opportunity to speak to those allegations before that information is disclosed or labeled as Laurie material.

I believe it is in the best interest of all stake holders for the Commission to establish a state-wide protocol to be followed by every law enforcement agency about how potentially exculpatory information is documented and maintained. This process will ideally remove any political animus that could affect smaller non-union departments (or any department) by putting an individual not directly supervising the officers or department in any decision making capacity.

While I don’t anticipate it will happen I would like to see our state protocols mirror those in the federal system, where the prosecutor makes a direct inquiry of officers involved in a case as to whether there is anything in the file that would bear on credibility in the particular case.

This would mean there is no “list.” Our goal as defense attorneys, despite apparent popular belief, is not to demonize or dig up dirt on officers, but to protect our clients’ rights. I believe getting rid of the “list” such as it is, would be a good step toward lifting the stigma of Laurie.

What I have heard from law enforcement representatives on the commission is that an officer identified as having something in their file that would be disclosable as Laurie material becomes blacklisted and unemployable. This is not the intent of the list and, I would argue, is a misuse of the list. If there is no list and each officer’s file is assessed on a case-by-case basis I think the stigma would be lessened.

I also think it is important to note that inclusion of any potentially exculpatory information in the personnel file does not per se mean it will be disclosed in court or even admissible at trial. And truth be told in over a decade of practice I have only once been advised that an officer had a Laurie issue. In that case the state opted to drop the case rather than disclose. When I later learned the specific conduct at issue it was not an issue I would have raised even if the case had proceeded.

The bottom line is that criminal defendants have a right to this information. As much as I agree that the officers should be afforded due process, I firmly believe that when balanced against the rights of criminal defendants, the rights of criminal defendants must prevail and the information must be disclosed. Failing to do so not only jeopardizes convictions and the right to a fair trial, but creates the appearance of an unbalanced, unfair process that finds a badge unassailable and that casts a pall over every officer’s credibility.

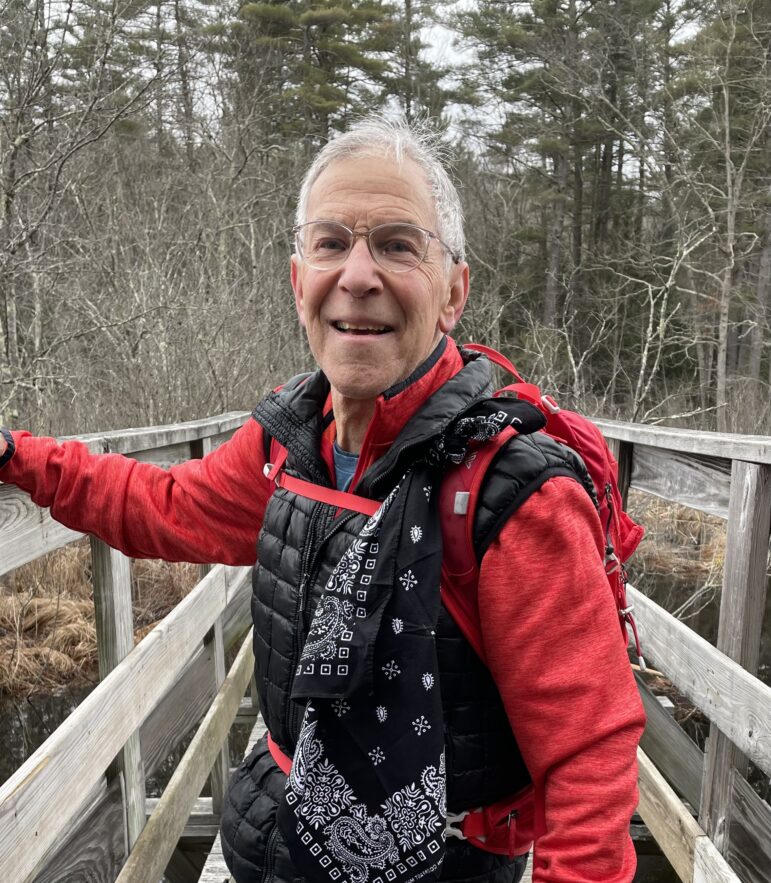

Concord Attorney Jim Moir, an expert on Laurie issues who testified at the commission’s hearing last week

What I would like to see out of this are two things. One, that law enforcement officers who are considered to be placed on the Laurie list have some mechanism where they can challenge the finding, giving police officers the same due process everyone should have.

The current system doesn’t do that. We’re not asking the court to come in and look at whether the officer had the particular personnel problem that they’re accused of. There’s a whole separate appeals process for that. The issue here is whether what the officer is found to have done is of such a nature or degree that the person should in fact be placed on the Laurie list. The officer should be able to challenge that and there’s no mechanism for that right now.

The other side of the equation is to try to make the Laurie list meaningful. Right now it is completely decentralized. No one is in charge of the list in the state. There’s no central data base for anybody to be able plug in to find it. Even prosecutors can’t find it.

That needs to be centralized. I would assume that the proper place for that is the Office of the Attorney General.

The list should be made public. Once an officer has gone through all due process appeal rights and someone is found to be appropriately on the list, there is no reason that should not be made public.

Londonderry Police Chief Bill Hart represents the New Hampshire Association of Chiefs of Police

While the conversation within the Commission regarding the Laurie list has been broad and free-ranging, a singular focus throughout has been to discuss, identify and perhaps create some due process protections for the police officers who may be designated for the Laurie list.

At a minimum, those protections might include notice of the designation for the Laurie list, and a right to some appeal to a neutral arbiter of that designation. Given that due process is nothing more than fundamental fairness, as a chief and a member of the NHCoP, it is a mechanism I can support.

There are other areas of concern with respect to the Laurie list which may be addressed in the forthcoming memorandum to be promulgated by the Attorney General’s Office. The Commission itself may address them as its life may continue beyond the Nov. 1 report date.

Stephen Arnold, represents New England Police Benevolent Association

The New England Police Benevolent Association has been leading the fight to abolish the “Laurie” list here in NH. The List, created by a Memo issued by former NH AG Peter Heed 11 years ago, has proven to be a failure of process. Officers have been subjectively placed on this career damaging and in some cases ending list, without any form of due process. Many Officers who face potential discipline for a myriad of reasons, that have “Laurie” potential, are placed on the list before their discipline cases are concluded. Once designated to the list, it has proven virtually impossible to be removed because no one will take responsibility to act. Additionally, there has proven to be no consistency, and in some cases deliberately harmful, amongst the Chiefs of Police when designating a “Laurie” candidate, because the memo failed to address a process.

A simple solution to this problem is to eliminate the “Laurie” list all together. When cases are prepared throughout the state a case preparation package is produced. There are cover sheets, to-do lists and many forms that usually accompany the case file. All there needs to be done is to add a form, standardize it state wide, which would require a police agency bringing a case forward, to identify if there are any potential exculpatory evidentiary issues associated with any officer attached to any given case. It’s that simple.

It is each and every officers constitutional right to challenge and face accusers like any other American citizen. The mere fact that a man or a woman pins on a badge is not a waiver of their constitutional rights. This process can be handled internally within the local departments through internal investigations. If deemed untruthful then the burden is on the department to notify prosecutors who have a duty to notify defense attorneys of any exculpatory evidence. It is a simple and logical solution to an 11 year old injustice.