By TERRY FARISH, InDepthNH.org

Mawouko Aboussa explained in his college entrance essay to the Art Institute of New York City that the reason he was interested in fashion design was because as a boy “we didn’t have any clothes.”

That’s one way he describes life in Benin, the country east of Togo, where his family fled to escape long violence at home. He was 3 years old. Aboussa’s family is from the village of Aného on the West African coast in the country of Togo. When I look up Aného, I read that it was the intellectual capital of the country. Aboussa’s Dad was a judge.

“We were one of the first African families in Concord,” Aboussa says. “We came in 2000.” In Concord his nickname became Moe. He came when he was in 7th grade from the refugee camp in Benin. About the UNHCR camp, he said:

“We were in real trouble. Everything was not all right. It was cool in the camp the first year. But then we notice people are missing. The locals did not want us. Us kids were trying to figure out the quiet murders. The sobbing as people were dragged to the bushes. So, we hung out with kids who could protect us.”

In the camp, though, he drew, a talent he got from his dad. “All of us were artists in the camp. Nothing else to keep us grounded. Chaos was our life. We did pencil drawing on paper. And we would sing a fulfilling song.” He liked to stitch with thread and a simple needle.

His first summer in New Hampshire – Aboussa was 11 – he tagged along with his younger brothers to Interlocken Camp (now called Windsor Mountain Camp) where Ellen Kenny first met him. Kenny was the camp nurse then, and teaching at Rumford School. (Now she’s the ELL teacher at Concord’s Broken Ground School.)

“Moe and his brothers loved soccer,” Kenny said and played aggressively on the campground’s big field.

In the night, “The boys came into the infirmary to draw. I still remember one of the pictures that either Moe or his brother drew of Lomé, the capital of Togo. It filled the page. It was full of color and stunning detail.”

Kenny said the boys were Concord’s first refugee kids. She spoke of “the well-meaning but ignorant mistakes we made as teachers, coaches, volunteers on this first wave of refugee children, simply by not understanding the depth of complexity, of trauma, of difference.”

She remembers over the years Aboussa struggled and didn’t have the support he needed. “He was always in trouble. In and out of jail.”

At Concord High, Aboussa was a soccer star. “Soccer to me was freedom. It was air to breathe. I wanted to be Pele. I didn’t know the English but if I scored, if I win the trophies for Concord, you have a lunch table you can sit at. You have friends that invite you over. For two weeks. Then you don’t see them anymore.”

Other students didn’t connect with him. He wanted to find a language to help him connect. He wanted students “to say a few things I could understand. Then I wouldn’t feel so lonely.”

“My high school days people provoked me to physical altercations because I was Black. Some altercations were more severe than others because it brought situations to fist fights so I would be arrested sometimes and the white kid didn’t. If I was getting drunk with a few people at a party where we all got in trouble I was the only Black kid in the group, so my situation was always worse.”

He went on: “I was getting jumped and beat up on because I’m Black.”

Kenny said, “The difference between him and the other top-level high school soccer players was that he had no one that knew how to ‘manage’ the trouble he was getting in. While they [white students] received scholarships to fine schools, Moe got out of town.”

Aboussa went to community college in Syracuse where he happened upon a promotional brochure: “New York is in need of young fashion designers.”

Life changing.

He would return to the art he did in the refugee camp.

In 2016 at the Art Institute of New York City, he loved learning about fabric and thread though he had to settle himself mentally to focus on the work.

His mom used to tell him, go sit alone, under a tree. Be still. In New York he learned that focus, a kind of meditation from which his art grew. He had another teacher while he studied at the Institute who told him, “You can use your art to do anything.”

Kenny said: “I think in New York City, in a new place, he re-invented himself.”

Now, four years back in Concord, Aboussa is making art inspired by his quest to tell the story of refugees in the world. “I create pieces to have in the home, on the body, to put in pictures. When I draw, I can bring joy into people’s eyes.”

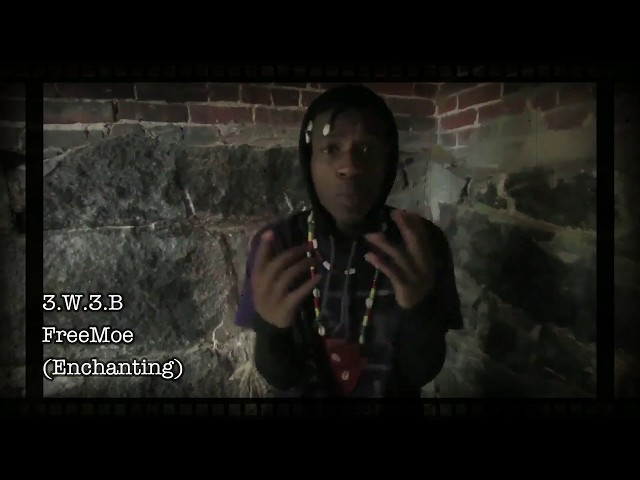

He transformed his American nickname into his stage name, FreeMoe, as he began to perform spoken art.

Aboussa’s work now includes clothing designs, dresses trimmed with kente cloth, and shoes with ornamentation using the bright colors of West African art.

His cardboard carvings depict the experience of refugees crossing through the landscape. One carving shows a row of people, their faces close up, grasping a bundle overhead; their eyes are fearful. “This gives people one-on-one time to look into the faces of the refugees.”

His wearable art includes a t-shirt he designed with symbols to describe who he is as the third-born child in a family of five kids, “3.W.3.B. Third World, Third Born.”

He’s turned to the jewelry of Togo as a muse and is creating traditional necklaces and bracelets of cowrie shells and beads. His studio is called 3.W.3.B Productions featuring his own Fugee Rap, telling stories of his memories when he was a boy in the Benin camp.

In “Enchanting,” he imagines the story of an elderly woman crying for help, “au secours, au secours,” the cry he remembered hearing as a boy.

Concord First Congregational Church recently featured “Enchanting” in one of the virtual gatherings they are offering during the pandemic, “Jazz Sanctuary.” Aboussa is using his art to tell the story of the journey of a refugee.

Aboussa will exhibit and sell his t-shirts, other wearable art, sculptures, and music on his website with the name 3.W.3.B currently in production.

“I want my art to encourage the younger me. I want to work with young people and tell them, Don’t be afraid of your past trauma. Why do I have to listen to Moe?” He’s speaking of his suffering Black brothers and sisters who he’s met and who have no hope.

His answer, “Because you cannot hide from your trauma. I know that stories can be told.”

Mawouko Aboussa’s rap, “Sorry” ends with

“…coming from the fire has a purpose

Purpose to finish education, hope to change the world“

Find FreeMoe:

Youtube channel 3.W.3.B Youtube https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJ0YivQ6MsJ6HELolXRxKAQO

FreeMoe Reverbation https://www.reverbnation.com/FreeMoe hiphop and rap

FreeMoe Facebook https://www.facebook.com/FreeMoe-454766054589421/

Moe Aboussa Facebook https://www.facebook.com/aboussa

Terry Farish is a freelance writer and novelist living on the Seacoast who writes for InDepthNH.org. She has written widely about contemporary immigration. Please contact her with ideas for immigrant and refugee stories, under-told stories, and stories that may not yet be part of the narrative of New Hampshire. She is especially interested in teen stories. tfarish@gmail.com