This story was co-published with New Hampshire Business Review

By Chris Jensen

GROVETON — Sometimes stuff just happens. Like you wind up owning a former paper mill in the North Country.

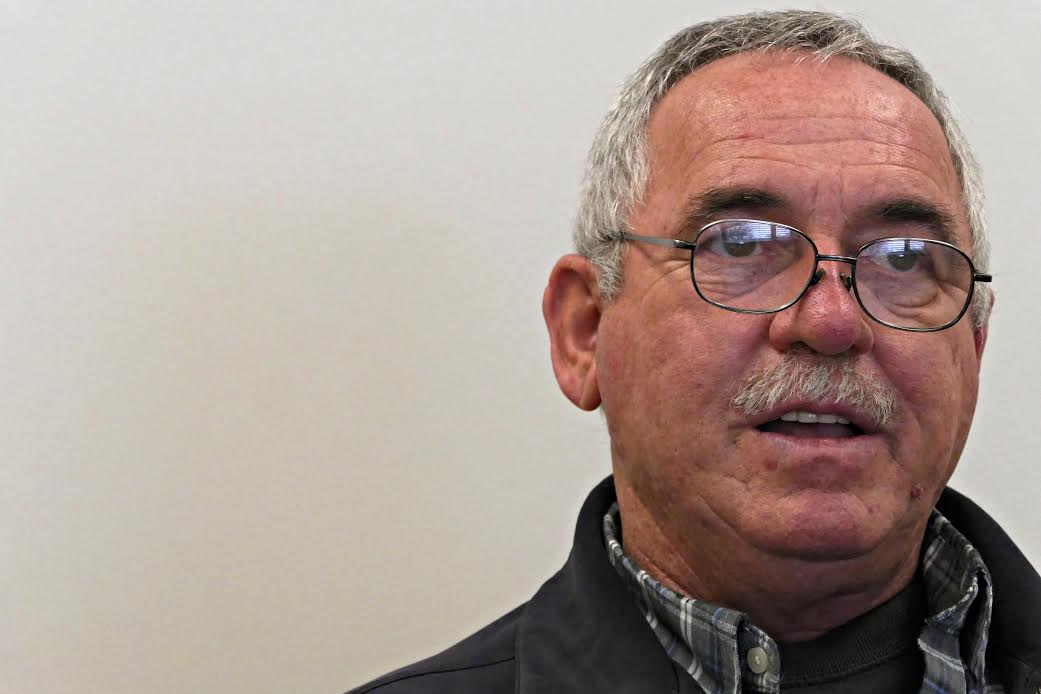

Bob Chapman didn’t plan on being the proprietor of the shuttered mill in Groveton, a cluster of about 1,100 people a little north of Lancaster.

Nor did he see himself playing a key role in bringing manufacturing jobs back to the hard-luck town.

But in January, NSA Industries LLC of Vermont located at the industrial park owned by Chapman. By next month it expects to have 45 employees, says James Moroney, its chief executive officer.

To a large extent the North Country has resigned itself to an economic future centered around tourism, so the return of those manufacturing jobs was a delightful surprise.

As was Chapman’s involvement.

“I got pulled in,” says the 60-year-old who came to the North Country almost four decades ago from Maine and opened a successful salvage business in Milan.

Not long after the plant closed, the equipment was removed, with some of it going to Vietnam. Chapman’s challenge was to take old facilities shown in this 2012 photograph and make them suitable for modern manufacturing. Photo by Chris Jensen

That happened bit by costly bit, as Chapman was caught up in a series of events beginning in 2011 with a $100,000 loan to a businessman who promptly died.

Now, he says, he’s invested about $15 million including labor and an incredible amount of wear and tear on machinery during the massive cleanup required to make the site suitable for businesses.

“I never, ever thought I would put that kind of money in a project,” he says. “But as we were going, it got deeper and we hit another hurdle and another hurdle and I am going, ‘My God.’”

The beginning

The Wausau paper mill closed at the end of 2007, its owners unable to cope with foreign competition. With about 300 employees, it had an annual payroll of about $13 million. Its closing crushed Groveton’s economy and to a large extent its hope for the future.

Shortly after that, Chapman and a handful of other businessmen started meeting to see whether they could buy the mill and find a company to reopen it.

But in 2011 a Bath entrepreneur, Charles Diamond, beat them to it. He wanted to turn it into a “Sustainable Technology Manufacturing, Research and Education Center.”

Chapman agreed to loan Diamond $100,000 for a down payment to seal the deal while Diamond pulled together the rest of the money. It seemed like a safe loan, but Chapman wasn’t considering mortality. Diamond became ill and died within a month.

It was Chapman’s bad luck that Diamond had given the $100,000 as a non-refundable deposit to the mill’s owner, Jerry Epstein, a businessman from New Jersey. Epstein told InDepthNH.org that he offered to sell the properly to Chapman.

Chapman wasn’t interested.

“There was a lot of asbestos, a lot of debris,” Chapman says. “It was too much of a gamble to try and do all that.” So, he wrote off that $100,000, describing it with a small shoulder shrug as “a piece of hard luck.”

Getting In Deeper

Instead, in 2012 the site was sold to Green Steel LLC of Scottsdale, Arizona, which demolished some buildings so it could salvage material such as steel. But Green Steel wasn’t happy with the work done by its demolition company.

So, in 2013 it hired Chapman to clean up the site. Chapman didn’t know it, but as his machines were sorting through the mess he was chugging towards ownership.

In 2014, it was clear to Chapman that Green Steel couldn’t pay his bill.

“It was in the millions they owed me,” he says. “How do you get your money back? The best way was get it in land and then you know you’ve got it.”

So, he wrote off the debt to Green Steel and became an owner.

Friends and family thought it was a mistake. “Everybody thought it was a bad move,” he says.

But Chapman figured he didn’t have a choice. “If I hadn’t made a deal on the land I had the chance of losing all of it,” he says. “I was getting in deeper and deeper.”

He saw his fiscal salvation in creating an industrial park. But what he owned was an apocalyptic jumble of debris left by the previous demolition company. And, the former mill site had neither water nor a sewage system.

He needed more money. So, he began borrowing from his other businesses, which included the salvage yard, a demolition company and a container business.

“I jeopardized all of them. That was a lot of money to pull out and put into a project,” he says.

What struck some in the North Country was that Chapman wasn’t from Groveton. This wasn’t the classic case of a local guy trying to help his hometown.

When Jim Tierney, Jr., who was then a selectman, heard that Bob Chapman purchased the mill his reaction was: who is that?

“I really didn’t know who he was,” Tierney says.

But Chapman’s action didn’t surprise Barry Normandeau, a businessman from the North Country who knows Chapman. He says Chapman figured Groveton was in his backyard, so he had to help.

The Wausau plant, which once bustled with activity and was the economic anchor of the area, fell to foreign competition. Photo by Chris Jensen

He describes Chapman as a workaholic who still uses a flip phone and is “very genuine, easy to talk to about anything. He knows everybody. It is amazing who he knows.”

And it didn’t surprise Benoit Lamontagne, a state economic development official in the North Country.

“He’s a guy with a huge heart who wants to help the North Country and believes in doing good things,” says Lamontagne.

Such benevolence aside, Chapman had to move forward to have any hope of recouping his investments. But there was something else in the mix.

“Once I saw the town was in desperate need of jobs, it was easier to come in and go for it. You know I wanted to prove to them I could bring the jobs there and I wanted to prove to them I wasn’t a quitter,” he says.

He says he was also encouraged because state officials, including those from the Department of Resources and Economic Development, were eager to help.

“They chase businesses to bring them and that is what pushed my interest to helping out,” he says. “Ray Burton was a good friend of mine and I must say (Executive Councilor) Joe Kenney is doing a good job of filling his shoes.”

And Chapman figured that the site had one important advantage: the ability to tap into a natural gas line and offer low-cost energy to tenants.

“The gas is going to be the key,” he says.

As the site was getting cleaned up, Mike Stirling, who manages the site, began showing it to potential tenants, but they wanted a facility with water and a sewage system and that would be expensive.

Whether that problem could be solved came down to Groveton’s faith in Chapman and Stirling. In particular, the issue was whether the town would borrow $400,000 so it could seek an additional $600,000 in federal funds to install the water and sewer.

But if Chapman and Stirling couldn’t attract any new businesses the fiscally stressed town would still have to pay off the loan.

That vote, Chapman remembers, was crucial.

“If the public stood behind the project, then the project was safe,” he says. “Otherwise there’s no need to keep dumping in millions.”

It passed by roughly a five-to-one margin. The town got the federal funds. And that led to NSA Industries setting up in Groveton.

For Chapman, getting that first tenant was enormous. “The cost is done, so that is the blessing,” says Chapman. “We have money coming in.”

And Stirling and state officials are trying to persuade other companies to locate there although they decline to provide any details citing non-disclosure agreements.

It’s taken a long time, but Chapman says a key part of his business philosophy has always been patience.

Tierney, who left the Groveton select board in March, says staying power is why Chapman succeeded while other owners failed.

“He was willing to invest the time and money and the energy. Whereas other companies I don’t think were,” he says.

“They were more looking for a return for their investors. And I don’t think their investors were necessarily willing to wait the length of time that Bob was willing to work at it.”

Chris Jensen covers the North Country for InDepthNH.org, a non-profit news outlet published online by the New Hampshire Center for Public Interest Journalism. Jensen worked as a reporter at The Plain Dealer in Cleveland for 25 years, has freelanced for the last decade to The New York Times and previously covered The North Country for New Hampshire Public Radio.