By Michael McCord

Late last year, a few months after Betsy Gray started working as an administrative staff member at Indian Stream Health Center in Colebrook, she was surprised when her supervisor shared some good news: her salary was bumped from $12 to $15 an hour.

“It was quite a blessing,” said Gray who had joined Indian Stream after more than a decade as an LNA or licensed nursing assistant. Gray and her self-employed husband have two young daughters and work hard to make ends meet.

“Obviously this means a lot for us but it also means that we can give more back to our schools and the community,” Gray said.

The Coos County native knows that higher-paying jobs in the North Country are far fewer than in the more populated, prosperous southern part of the state.

According to 2015 U.S. Census figures, the median family income in New Hampshire is $70,303 which is almost $15,000 above the U.S. average of $55,775. In Coos County, the median family income is $42,312 and 16.1 percent of the county’s almost 31,000 residents live in poverty.

“I’ve seen people in my family work almost all of their lives and never get to $15 an hour,” Gray said. “I almost cried when they told me about the raise. I’ve never heard of something like that before.”

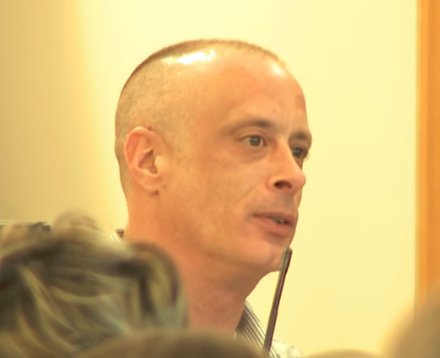

Indian Stream CEO Jonathan Brown didn’t mean to bring employees to the verge of tears when he approached the organization’s board of directors last year with a proposal – establish a minimum wage of $15 an hour. But he did understand the importance to Indian Stream and the community.

“I’ve been there,” said Brown who came to Indian Stream in 2006 as an IT specialist and became CEO in January 2015. “My wife and I lived in rural Maine and we learned what it’s like to struggle to make the apartment rent and make ends meet working in minimum-wage like jobs. You live paycheck to paycheck and never seem to get ahead.”

Indian Stream is a federally qualified health center and serves the health-care needs of thousands of residents in the North Country and in portions of Vermont (where they have a second location in Canaan) and Maine.

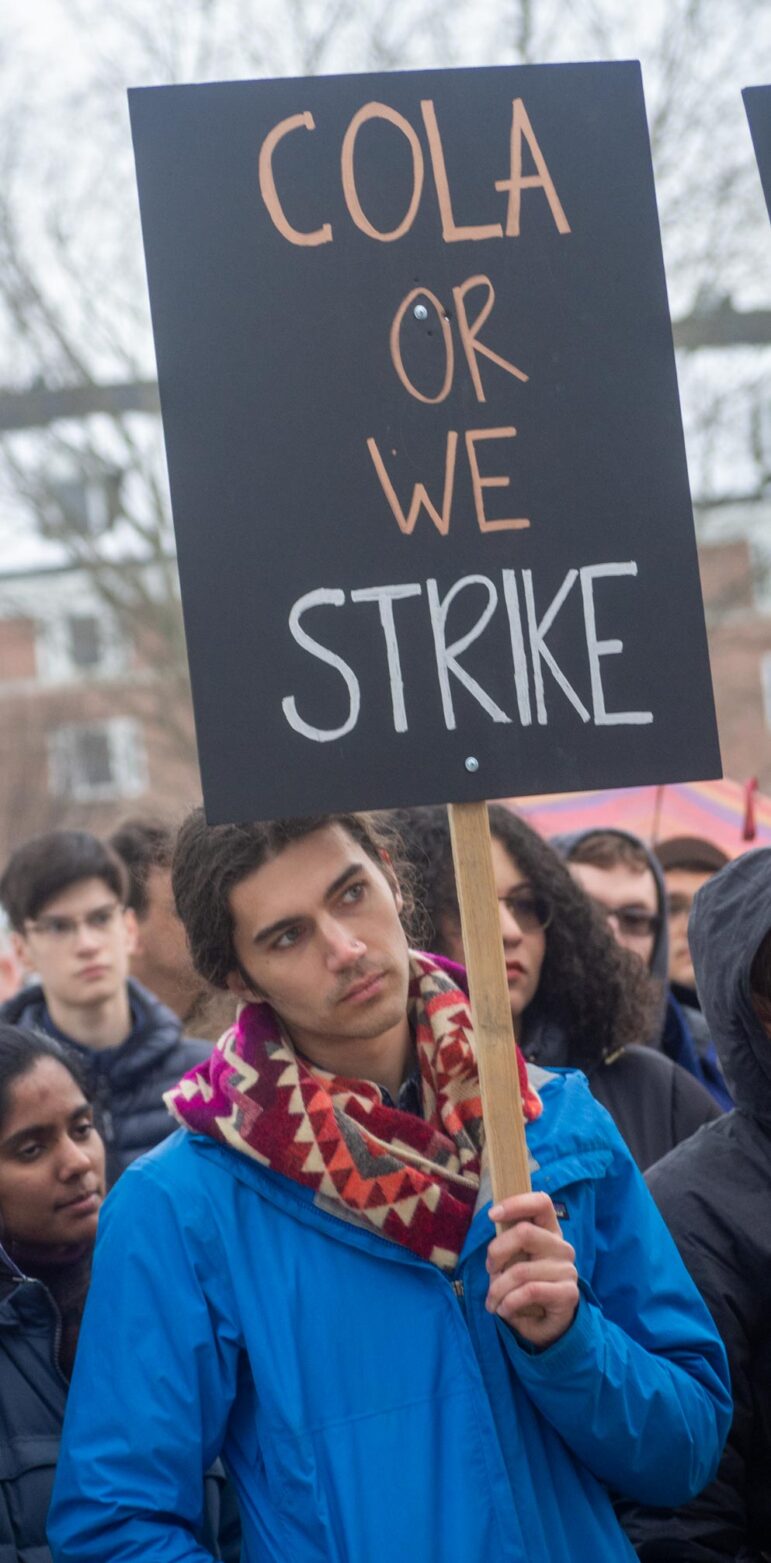

During the heat of the 2016 presidential campaign and as more focus was on raising the federal minimum wage (last increased in 2009 to $7.25 an hour), Brown said he did his own research about a living wage.

The city of Seattle had already raised its minimum wage to $15 an hour. Likewise, voters in Arizona, Colorado, Maine, and Washington approved measures to raise their minimum wage (Maine has set a goal of $12 per hour by 2020). California has a statewide goal of $15 an hour by 2022 while New Hampshire lawmakers voted down a recent bid to raise the state’s $7.25 an hour minimum wage.

Last year, Brown talked to his finance staff and then to the board about the measure to start employees at $14. 50 an hour and raise it to $15 an hour after a three-month probation period. The measure was approved and went into effect in the fourth quarter of 2016.

“We all know the cost of living goes up,” Brown said. “Food and transportation expenses continue to rise. This wasn’t about us leading the way but to state publicly to our employees and the community that human capital is our most important asset.”

The definition of a living wage has a wide number of variables and is region specific. For example, the living wage calculator created by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said the minimum living wage for a family like Betsy Gray’s (two working adults full time with two children) would be $13.97 an hour or a total household salary of almost $59,000 annually.

By comparison, the same variables for the same family unit in Rockingham County would be $15.44 an hour or a total household salary of $64,000 annually. But Healthy Monadnock 2020, an organization in Cheshire County, believed the MIT calculator was too low, especially for single adults and single-parent families, and urged a coalition of business members to enact a $15 an hour minimum wage by 2020.

The Monadnock Living Wage Group was formed to calculate region-specific needs and to encourage more business support.

In a June 2016 New Hampshire Business Review story, Healthy Monadnock 2020 director Linda Rubin said a higher living wage is directly connected to better regional health outcomes.

“If people are earning better wages, they’re going to use that additional money on the kinds of things they need to live – health care, housing, education and basic needs,” Rubin said in the story. “If you have safe housing, you’re going to be in a better position health-wise.”

At Indian Stream, Brown said about 10 employees of the staff of 65 were impacted and there was overwhelming organizational support for the living wage policy.

“We look at our mission as a federally qualified health center. Our focus is on the health and wellness of the community and it must extend to our staff,” Brown said.

“It’s not a significant dent overall but it is significant to the families of our employees. While it’s difficult to measure bottom line impact, I don’t think there’s any doubt about the boost in company morale and productivity.”

Find out more about Indian Stream Health Center.

Learn about the MIT living wage calculator for New Hampshire.