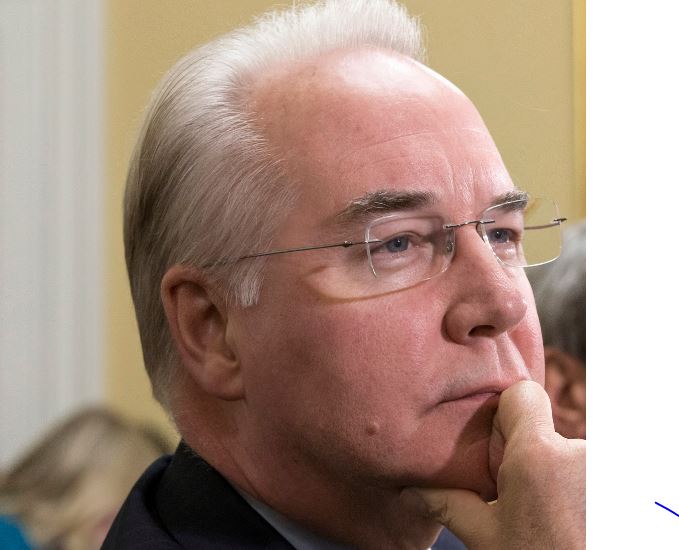

Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.), Donald Trump’s pick to head the Department of Health and Human Services, has come under fire for buying and selling shares companies in the health care industry whose fortunes he could affect through his perch in Congress, and for intervening with regulators on behalf of some of his donors in the medical field.

Turns out the Federal Election Commission isn’t happy with him either, calling out the nominee for lousy disclosure on the campaign finance reports he turned in last year.

A Jan. 8 letter from the agency to Price’s campaign points out that there is no employer or occupation given for many of the donors listed on his most recent report — in fact, it comes out to about 30 percent. Instead, the campaign entered “Information Requested” in the corresponding column — which doesn’t satisfy the FEC’s requirement.

Over the entire two-year 2016 cycle, Price failed to give any info about a donor’s occupation for $111,577 in contributions through Nov. 28, or 13.2 percent of all the money he raised. Donors of an additional $1,350 are labeled vaguely as “businessman,” “entrepreneur” and the like, descriptions that don’t exactly clear up the picture.

|

Full Disclosure | $732,863 | (86.6%) |

|

Incomplete | $1,350 | (0.2%) |

|

No Disclosure | $111,577 | (13.2%) |

Compared with his peers, Price looks pretty dismal. Among members of Congress who won their races this cycle, he’s among the 25 worst on quality of disclosure. The average figure for “full disclosure” — no missing data — for these lawmakers is 96.2 percent, and the median is 98.1 percent, more than 10 percentage points above Price. And the Georgia Republican’s 13.2 percent of entries without a company or occupation is astronomical compared to the median of .51 percent, or average of .83 percent, for all Congress.

Reporting employment data for all congressional winners in 2016

The worst of the bunch is Republican Claudia Tenney, newly elected to New York’s District 22, whose entries were incomplete for $141,000 in donations, or 36.9 percent of what she raised. Rep. Mike Pompeo (R-Kan.), another of Trump’s tapped picks for his administration, failed to properly report only 1.1 percent of donors’ occupations. Four members of Congress boast incomplete data for contributors giving what adds up to millions of dollars: Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) with $7.3 million, Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) with $2.1 million, Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) with $1.4 million and Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.) with $1.3 million. (To play around in the data yourself, see our spreadsheet.)

The election agency told Price to demonstrate that “best efforts” were made to get all the required info. Best efforts probably aren’t as strenuous as you think they are. Price only needs to ask donors one more time for their job titles. If the donor refuses, Price is off the hook.

Price is supposed to prove he asked that second time; otherwise, he risks a civil penalty, could have to take an FEC compliance course or face an audit, according to FEC press officer Christian Hilland. (The FEC cannot speak specifically about ongoing cases.)

Rep. Price’s campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

The largest incomplete line item in his last report, a $2,700 contribution in October, came from a Robert A. Yellowlees in Atlanta, Georgia. A quick Google search pulls up a page for a member of the Emory Global Health Advisory Board with the same name. This Yellowlees is the retired board chairman of Global Payments Inc., NDCHealth and National Data Corporation, and starting his career with IBM. He also serves on the boards of Woodruff Arts Center and the High Museum of Art and Aperture Foundation. (His family, incidentally gave $400,000 to the High Museum of Art in 2014.)

What’s the big deal about this kind of missing data on donors?

“Congress required campaigns to seek occupation and employer information from campaign contributors so the public would know who was supporting each candidate,” said Brett Kappel, a partner at Akerman LLP. “The information allows the public to know whether a candidate is supported by members of a specific trade or profession as well as whether they are supported by a specific company.”

Employer data is key to the work of the Center for Responsive Politics. Political giving patterns by employees can show how an organization is trying to exert influence in Washington, since corporations cannot give through their own treasuries and their PAC contributions often tell just part of the story. While we can’t know the motivation behind every contribution, the Center’s research has found correlations between individuals’ contributions and their employers’ interests.

With this required field left blank, voters are left with an incomplete picture of the interests that may be attempting to sway their elected officials.

Price’s confirmation hearing is tentatively set for Jan. 18.

Researcher Alex Baumgart contributed to this post.