There is no more essential act in a democracy than voting. But making sure that the balloting is open to all and efficiently administered has been, at best, a low priority for many state legislatures, a victim of misplaced priorities and, at times, political gamesmanship.

Historically, newsrooms have focused on covering the outcome of Election Day, relegating voting snafus to be followed up later, if at all. Today we’re announcingElectionland, a project to cover voting access and other problems in real time. The issue is particularly urgent this election year, as states have passed laws that could affect citizens’ access to the ballot box.

We’ll leave the horse race to others and focus on the ways in which problems prevent people from voting: Which voters are getting turned away (and why)? Where are lines so long that people are giving up? Is there actually any evidence of people casting fraudulent votes?

To answer these questions we’re teaming up with a group of media partners to create a virtual newsroom that will produce stories on voting problems as they happen, and distribute leads about voting problems to local journalists who can follow up on them. It is our hope that this journalism will have immediate impact, helping people who might otherwise have been turned away to cast their ballots.

The rules for voting are changing fast. A 2013 Supreme Court decision, Shelby County vs. Holder, made major changes in the Voting Rights Act, ending the requirement that states and counties with a history of discrimination pre-clear changes to election laws. A number of states moved immediately to revise their laws, including North Carolina, which rewrote its rules to do what state GOP Executive Director Dallas Woodhouse described as “attempting to rebalance the scales” in favor of Republican voters.

North Carolina’s law was struck down. The constitutionality of other states’ laws is still being litigated (see our election lawsuit tracker), but as many as 15 states will vote this year under laws that have never been tested in a presidential election.

“The question is not whether problems will arise in November 2016,” said a Caltech/MIT report on election administration, “but where they will occur, what form they will take, and how significant they will be.” The report said it is likely that some localities will experience voting problems comparable to the weeks of legal fighting over who won Florida’s presidential vote in the 2000 election.

There are numerous ways in which voting can go awry. One of the more commonplace, excessive wait times, plagues many polling places — notably Maricopa County, Arizona,during the primaries this spring. Long lines can cause voters to give up, especially working voters who have only a limited amount of time available to cast their ballots.

A 2014 report by the Presidential Commission on Election Administration concludedthat nobody should wait more than 30 minutes to vote. Yet in many places around the country, the wait can be far longer. In Florida, for example, the average wait in 2012 was 39 minutes, according to researchers Charles Stewart and Stephen Ansolabehere. Those same researchers estimate that the total votes lost nationwide because of long lines in 2012 was between 500,000 and 700,000.

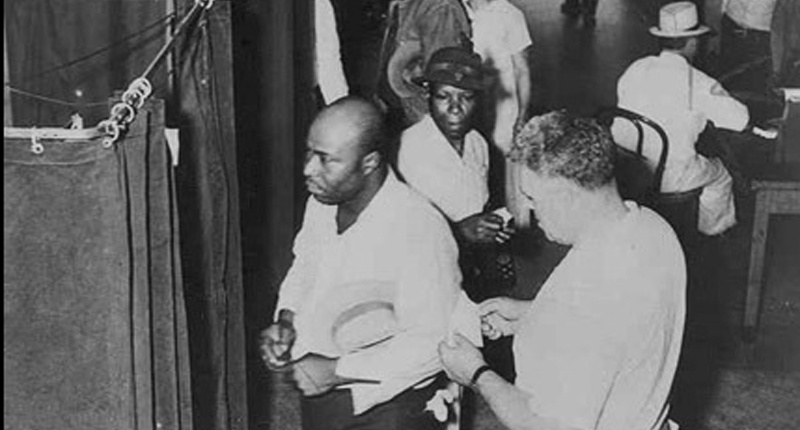

A recent study by the Brennan Center for Justice found that long waits to vote are not randomly or evenly distributed. African-American and Hispanic districts are oftendisproportionately affected by long lines.

There are also registration problems that can prevent people from voting. In Brooklyn earlier this year, about 120,000 Democratic voters were purged from the rolls and were unable to vote in the primary. WNYC News found that voters with Hispanic surnameswere “purged at a rate 60 percent greater than everyone else.” Officials at the New York City Board of Elections acknowledged that voters were improperly removed but denied any political or ethnic motivations.

American elections are decentralized affairs that unfold in tens of thousands of locations. To have a sense of what’s happening nationwide, you need be able to cover each of these as a discrete story, an effort beyond the scope of even the largest news organizations. To track voting in 2016, ProPublica is working with a coalition of newsrooms and technology companies with disparate skills and audiences. They include:

- The Google News Lab, which is providing technology assistance as well as financial support.

- The First Draft Coalition, an organization that specializes in verifying facts, images and video that emerge on social media. First Draft will help lead the data verification efforts, including training a team of journalism students.

- The WNYC Data News Team, which is helping plan our breaking coverage and coordinating with dozens of public radio stations around the country, including WLRN in Miami, KERA in Dallas, WHYY in Philadelphia and KPCC in Los Angeles.

- Univision, which will look closely at Hispanic voters who are said to experience a disproportionate share of voting problems.

- The USA TODAY network, whose 92 local markets include some two dozen in areas with a history of problems with long lines.

- The CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, whose students and faculty — including from their Social Journalism program — will staff a live newsroom on Election Day, along with students from a dozen other schools. The high-tech CUNY newsroom in midtown Manhattan will be the home of our national newsroom on Nov. 8.

We’ll be gathering information about voting problems from many sources, including social media, Google search trends, and data from Election Protection, a project of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, which receives calls from voters around the country about voting issues.

We’ll also be asking for your help: In the coming weeks we’ll be announcing a way for citizens to tell us about conditions at their polling places on Election Day and during early voting.

Using techniques and technologies created by the First Draft Coalition, we’ll filter, verify and collect credible clues about voting problems and hand them off to one of the hundreds of local journalists assigned to cover election day. They’ll be able to follow up on problems and write stories that can be distributed online not in the weeks after the election but while the polls are still open. We’ll collect their stories and cover the national picture on propublica.org.

To be sure, U.S. elections are, for most voters, very well run, and election officials succeed despite difficult instructions, resource constraints, and impatient voters. Experts across the political spectrum dismissed Republican candidate Donald Trump’s concern that a presidential election could be “rigged” through fraud.

But they agree that the injection of that concept into the public debate makes it all the more important for journalists to cover in detail exactly what happens on Election Day. And there’s a more fundamental point: Voting is one of our few constitutionally enshrined rights as Americans and we view it as newsworthy when anyone is denied a chance to cast their ballot, even if it doesn’t change the ultimate outcome.

Our plan is to launch in time for the start of Ohio’s early voting on Oct. 4 and to ramp up coverage until Election Day.

If you are a journalist in a newsroom looking to cover voting, or if you’re a non-journalist who’d like to help gather data on Election Day, you can sign up atpropublica.org/electionland.

If you’ve got questions about how Electionland will work, head over to our FAQs.