Nancy West Photo

Attorney General Joseph Foster earlier this year released more than 7,000 heavily redacted pages of his investigation into former Rockingham County Attorney Jim Reams. Of the 2,594 pages in the first batch to be released, 1,338 were withheld, according to Foster’s office.

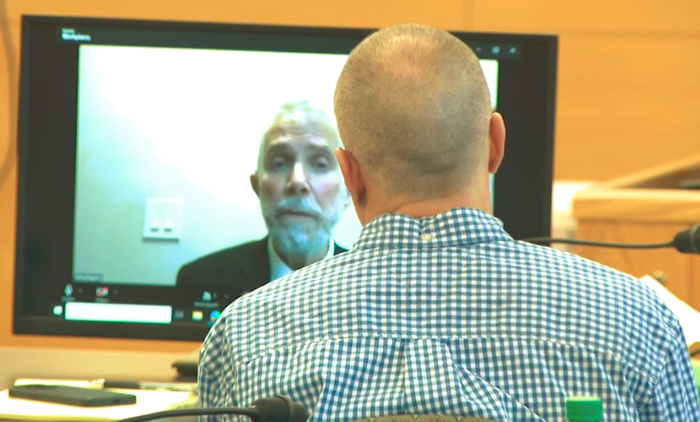

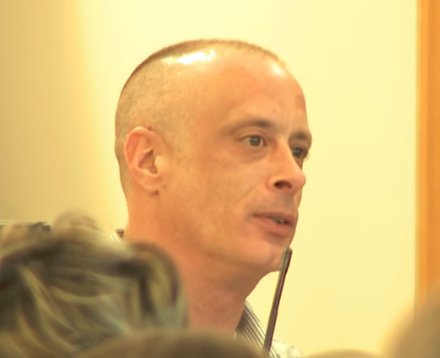

Concord Attorney Tom Reid is still fighting to get a copy of the complete investigation that prompted Attorney General Joseph Foster’s failed attempt to remove former Rockingham County Attorney Jim Reams from office two years ago.

Reid served as Reams’ deputy when Foster locked Reams out of his office and temporarily suspended him on Nov. 6, 2013. Although Reid was never the target of the probe, he and a victim advocate were also suspended with pay that day.

“I want these people held accountable,” Reid said during a recent interview. “Any elected official could be targeted by the Attorney General’s Office if they are willing to engage in this type of smear campaign.”

The Attorney General’s Office exaggerated and made gross misrepresentations in trying to oust Reams, a Republican from Hampton who was first elected in 1998, Reid said.

“This matters because whatever was done wasn’t done objectively,” said Reid, who resigned two months after being suspended.

This time, Reid is appealing to the state Supreme Court. Reid claims Merrimack County Superior Court Judge Larry Smukler was wrong to deny him the original investigation before most of its 7,399 pages were blacked-out.

Foster, who was appointed by Democratic Gov. Maggie Hassan, claims the many redacted pages were exempt from disclosure under the right-to-know law because they contain “personnel” information.

Reid argues that it’s unfair for Foster to have alleged in court while trying to remove Reams that he was conducting a criminal investigation, and only later claim it was a personnel matter in order to shield the records from public scrutiny.

“The question really is, can you have an appointed official remove an elected official and undermine the will of the electorate in a democracy and not be accountable to the people?” Reid asked.

Reid said in his Supreme Court notice that limiting access to the complete probe unreasonably restricts the public’s ability to hold the attorney general accountable, to find out why he tried to remove Reams, and “to determine the extent of improper conduct occurring in the removal of an elected official.”

The March 11, 2014, removal complaint Foster filed against Reams contained allegations of an ethical violation, financial mismanagement, and gender discrimination. The state later said there was an ongoing criminal investigation, but no criminal charges were filed.

The merits were never heard and no findings were made. Superior Court Judge Richard McNamara ordered Reams back to work the following month when it was clear no criminal charges would be filed.

“For the reasons stated in this order, the Court finds that Reams’ current suspension is unlawful, and that he must be reinstated as Rockingham County Attorney, and provided access to the County offices,” McNamara wrote.

McNamara also wrote: “Allegations, no matter how inflammatory, are not a substitute for evidence.”

Foster appealed to the state Supreme Court, which declined without comment to hear the case.

Reams returned to work and retired June 17, 2014, after the Rockingham County Commissioners agreed to pay him through the end of his term.

Reid originally won his public records lawsuit against Foster in January in Merrimack County Superior Court in Concord.

Judge Smukler had ruled that Foster violated the state’s right-to-know law by failing to turn over the Reams investigation to Reid in a “timely manner” after seven months and awarded him costs. He did not find Foster acted in bad faith.

When Smukler later ruled in Foster’s favor regarding the document redactions, Reid filed the notice of mandatory appeal with the state Supreme Court.

Reid insists the Attorney General’s Office was out to get Reams because he had been critical of the office and its drug task force.

The Reams investigation involved gender discrimination complaints that had been made more than a year earlier, Reid said. Some dated back to 1999 and all had been dealt with previously by the county, he said.

“They (Attorney General’s Office) used the grand jury to drag in some female employees to testify and humiliate them in their quest to get Reams,” Reid said.

State and federal authorities scrambled to find criminal wrongdoing, but failed to do so, he said.

Reid is likely in for a long haul before the matter is resolved at the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court spokesman Carole Alfano said the court requested the hearing transcripts late last month and the turnaround time is usually 45 to 60 days. A briefing schedule will be set after that.

Deputy Attorney General Ann Rice, who responded to requests seeking an interview with Foster, said the office had no comment and would state its position when it files its brief in the state Supreme Court.

In a letter to InDepthNH.org releasing the first round of 2,594 documents, the Attorney General’s Office said digital recordings of interviews were not disclosable without redaction. That would cost the requester “several thousand dollars.”

Transcripts of the digital recordings of interviews were disclosable, the letter said, with “redactions of exempt information – e.g. personnel information, privacy (including financial, medical and education), and grand jury, RSA 91-A-5, I and IV.”

RSA 91-A is the state’s right-to-know law that deals with the disclosure of public records.

RSA 91-A-5, I and IV exempt documents from grand or petit juries and “records pertaining to internal personnel practices.”

When Reid resigned, Foster issued a news release saying Reid had cooperated in the Reams probe.

“Mr. Reid was not the target of a criminal investigation and our investigation has not revealed any evidence that he engaged in any criminal conduct,” the release states.

Still, Reid remains determined to make sure the unredacted investigation becomes public.

“I firmly believe the only reason they put me out was so they could do a complete witch hunt unfettered. There was no reason to put me out, too,” Reid said.

Reid’s notice asks the state Supreme Court to address whether Smukler was wrong to deny him access “thereby unreasonably restricting the public’s access to information about its public officials…”

Foster also “had selectively redacted portions of his investigation, revealing some personnel related information while redacting others,” Reid wrote.

The court was also wrong, according to Reid, for failing to address Foster’s demand for 20-cents per scanned page produced in digital format “where the majority of the pages subject to the charge are completely blacked out…”

“The public should have great pause if people in the Attorney General’s Office are willing to engage in this type of nonobjective misrepresentation and conduct an agenda-driven investigation,” Reid said.

“This whole situation is absurd.”